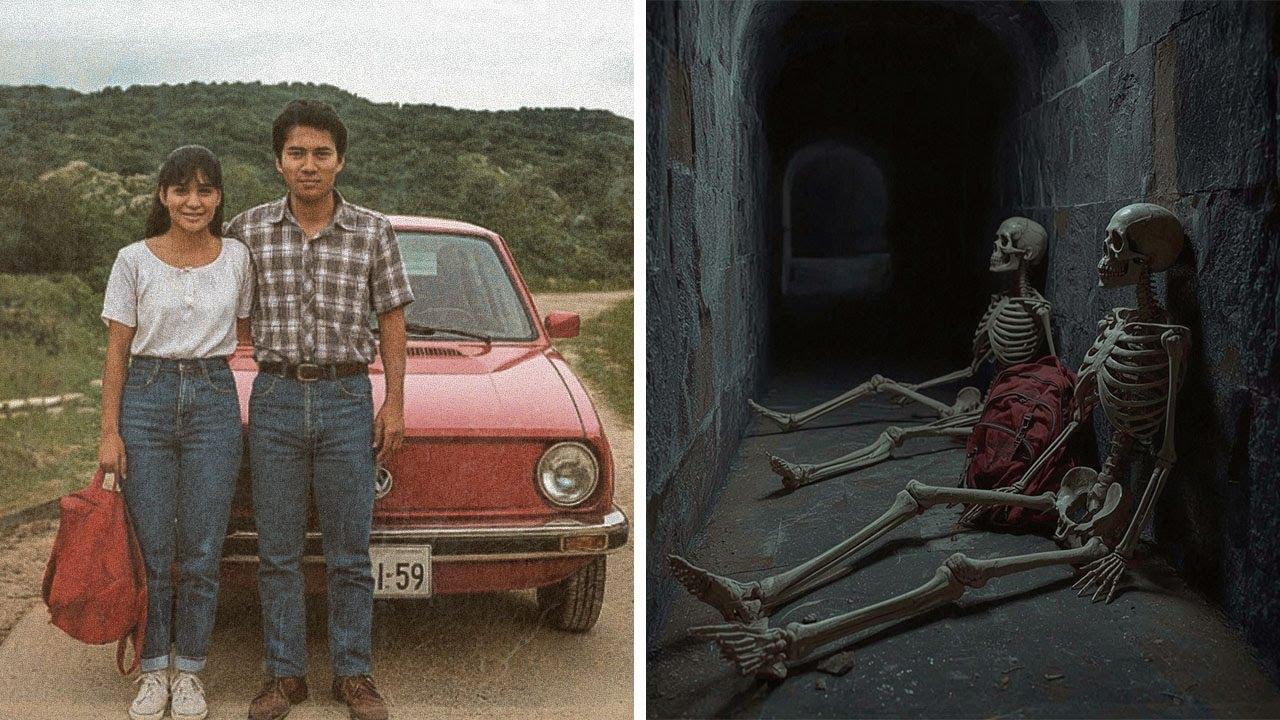

For years, the last memory the Ramírez and Vargas families had of their children was a simple but vibrant image. Luis and Marisol smiling in front of a red car parked on a dirt road. Behind them, the green of the Zongolica mountains stretched out like a promise of freedom and silence. The red backpack Marisol carried on her shoulders looked new, still vibrant in the morning sun. It was the beginning of a weekend that for everyone else passed like any other, but for them, they never returned.

Luis Eduardo Ramírez Ávila was 28 years old. Born and raised in Chalapa, he was always discreet, methodical, and possessed a certain fascination for technology. Working as a telecommunications technician, he spent a good deal of time in the field adjusting antennas, troubleshooting signal failures, and entering places few knew about. Meanwhile, Marisol Vargas Gallardo, 25, taught at a kindergarten on the outskirts of Chalapa. Her students adored her, not only for the games, but for the sweet and patient way she explained things.

Marisol was also an only child, and perhaps that’s why her parents were always more attentive, almost anxious about her absence. On Friday, April 8, 1994, Luis and Marisol left the city with the plan of spending just two days away. He had finished an installation earlier that week, and she had gotten an early day off. The decision to travel was made the night before. No reservations, no booked inns, just light clothing, food, a thermos, and threw everything into the trunk of their 1991 Volkswagen Caribe.

A used car, but one that Luis kept in excellent condition. They filled the tank before leaving, and they notified their parents that they would return on Sunday the 10th in the late afternoon. At that time, the Zongolica Mountains were still seen as a little-explored refuge. Tourists from outside rarely appeared there. It was more common to see young people from Orizaba or Córdoba trying to hike or discover small hidden waterfalls. Luis and Marisol had already been to other mountainous regions, such as Cofre de Perote and Chico, but they had never ventured so deep into the Sierra’s dirt roads.

According to records and later accounts, they continued south on the federal highway to Tequila, Veracruz, where they were spotted by a man from a local ejido. It was Saturday morning, and he remembered the pair well because the girl was wearing a red backpack with a striking yellow ribbon. They asked for a route to a waterfall; they didn’t mention its name. The man directed them to an old, rarely used trail that climbed through a deactivated mining area.

He never saw them again. From then on, everything faded away. On Sunday, as agreed, the families waited for some sign of his return. At dusk, still hopeful, they called close friends. When no one answered, Luis’s parents went to the municipal office and officially registered his disappearance. The report was filed in Shalapa at 8:45 p.m. on April 10. The officers recommended waiting until the next day, a common practice at that time. But the parents didn’t wait.

That same night, they took the car and continued toward the last known address. By Monday the 11th, a small network of acquaintances was already searching for clues between the cities of Tequila, Songolica, and Atlahüilco. A friend of Luis’s, who worked at a community radio station in Orizaba, mentioned the case on air, and the news spread quickly. Volunteers, neighbors, and even truck drivers offered help. However, with no itinerary, no fixed destination, no safe path to follow, everything seemed like a vast void.

State authorities only became involved after three days, when the case was already taking on the appearance of a mystery. The formal search began on main roads, dirt roads, trailheads, and riverbanks. Helicopters from the Veracruz State Public Security Service (SSP) flew over some more remote areas, but the rugged terrain and dense vegetation made visibility difficult. The distinctive red car was never found. There were no accident remains or tire marks in suspicious areas. It was as if the vehicle with the two inside had evaporated among the trees.

As the days passed, rumors began to emerge. Some said the region had a long-standing reputation as a smuggling route. Others spoke of groups hiding in the mountains to escape the police and disliked curious onlookers. In the following weeks, residents reported strange sounds, distant screams, and lights that suddenly went out, but none of these stories yielded any concrete clues. An important detail is that among the places considered dangerous were the region’s abandoned mines.

Many of them had been deactivated in the 1980s when artisanal mining became unprofitable. Some were still used by mountain goats or as shelters for homeless people, but no one ventured deep into them. The fear of collapse was real. None of the search teams were authorized to explore these structures in depth. Even so, family members insisted that something had happened there, somewhere no one was willing to look closely.

Little by little, press coverage disappeared. The poster with photos of Luis and Marisol was removed from many businesses after two months. Every anniversary of their disappearance, a mass was held in Shalapa with a few acquaintances in attendance. Marisol’s mother kept hope alive, but she no longer mentioned her daughter’s name out loud. The last trace of life, that image from the road saved in a developed print. Luis in the plaid shirt, Marisol in white sneakers.

Behind them, a seemingly peaceful road concealed perhaps one of the most terrifying stories of the 1990s in Veracruz. On the morning of Monday, April 11, 1994, the municipal delegate of Shalapa wrote down Luis and Marisol’s information on a piece of notebook paper. At that time, the system was not yet digital. The disappearance was recorded as voluntary absence without serious consequences, a common expression when there were no immediate signs of a crime.

But from the beginning, the parents knew this wasn’t a simple escape, much less a mistake. Luis was methodical, and Marisol would never disappear without a trace. That same day, Marisol’s father managed to convince an acquaintance in the state police to pass the information to the Orizaba police station. This began a small, parallel mobilization. Three civilian patrols were deployed to mountain communities: San Sebastián, Atlahuilco, and a secondary route that passed through Tenango.

Still, the search was scattered. The region was vast, rugged, riddled with access roads that either ended in nothing or led to trails used only by local residents and hunters. On the third day of searching, a piece of information brought hope, but also more mystery. A farmer from a common land between Tequila and Coxititla named Jacinto, an elderly man of few words, claimed he had seen a couple resembling Luis and Marisol the previous Saturday, around 10 a.m.

They were buying gasoline that he himself sold in plastic bottles, a common custom in areas without formal gas stations. He particularly remembered the girl for her red backpack. He said the young man asked for a route to see a famous waterfall nearby, but couldn’t name it. Jacinto responded with what he knew. There was indeed an old trail that led to a nearby waterfall, but it crossed a deactivated mining area. A road used in the past by miners transporting cargo with mules.

He pointed out the address, but made it clear it was dangerous if no one knew him. This information not only confirmed their survival as of Saturday morning, but also reinforced the families’ worst fear: that they were lost in a forgotten area, without radio coverage and no way to call for help. In the following days, the search intensified. A group of volunteers organized by local radio stations joined members of the Orizaba Red Cross, while helicopters from the Ministry of Public Security began mapping trails and clearings.

Sniffer dogs were brought in from Córdoba. The car, a red 1991 Ubi Caribe, was the easiest object to identify. Any metallic reflection on the slopes or the bends in the river could be a clue. But nothing turned up: no tire print, no piece of cloth, no trace of food or remains of a camp. One volunteer even suggested they had been taken. The idea seemed absurd at first, but as the days passed and the absence of any sign became unbearable, the most somber hypotheses began to gain strength.

At the end of the second week, a field agent from the State Attorney General’s Office recommended seeking out less-explored areas, trails with less access, natural caves, and especially old abandoned mines. But that was a breaking point. Many of the local guides refused to enter the mines. According to them, it wasn’t just a fear of collapses, although that was real. There were stories of makeshift crosses still standing at some mine entrances. Others had marks at the entrance made with lime or red paint indicating past deaths.

Some said that in the 1980s, these mines had been hideouts for criminals. Others spoke of settling scores between smugglers and former private mine workers who never received what they were owed. What was known was that officially, none of these mines were considered safe, and so searches there were superficial. Only in the most accessible areas were brief entries made with flashlights and guides. Nothing was found. In the third week, the case began to cool down.

The field commander informed the families that there were no resources to maintain so many patrols and deployed personnel any longer. Press support also began to wane. With no news, no leads, no bodies, interest was fading. The volunteers left one by one. Starting in May, only the family members continued to go to the region weekly. They stopped for tequila, spoke with residents, retraced previously explored paths. Luis’s father carried crumpled maps, marked points with a pen, but always returned home with the same question.

Where did they go that no one else saw? Marisol’s mother, for her part, kept a backpack identical to her daughter’s, hanging in the room, washed, folded, untouched. She said that one day Marisol would return and that she wanted to show her that everything was as it had been. In the following months, new stories emerged. All vague, none reliable. A man speaking a zongolica (a local language) said he’d heard gunshots in a mine behind him. A woman claimed to have seen two people sleeping near a stream and that it could be them.

But time passes, and memory also betrays us. Nothing led anywhere. At the end of 1994, the Veracruz Public Ministry officially filed the case as an unsolved disappearance. All that remained was the file: 32 pages of testimonies, old photos, reports, and a list of possible routes. Inside, a Post-it note handwritten by an agent at the time. Checking abandoned mines. Low priority. No one touched it again until 2005. At the end of 1994, with the searches officially over and the case filed as a disappearance without criminal evidence, time began to do what it always does to the unexplained.

It covered everything with a kind of invisible dust, a silence that spread first to the authorities, then to the neighbors, until it reached their own memories. For the next three years, the name of Luis Eduardo Ramírez Ávila was no longer mentioned in radio broadcasts or in SSP communiqués. The photo of the Budravobo Caribe Rojo faded from the walls of the region’s markets. No one missed that couple who had gone away for a weekend and never returned.

But within families, absence was something alive, almost physical. Luis’s father set up a small archive in the closet at home. Newspaper clippings, scratched maps, cassette tapes with interview recordings, and even small stones collected from regions they passed through during the searches. He said that one day someone would be able to put it all together and understand. For her part, Marisol’s mother began to carry a laminated copy of the photograph, where her daughter appears smiling next to her boyfriend.

He showed her to strangers, bus drivers, and vendors. It was a painful gesture, not because he still hoped to see her alive, but because he couldn’t bear the thought of anyone else remembering. Starting in 1997, new rumors began to surface. A young man who worked hauling firewood said he had heard years earlier that a mine between Atlahco and Zongólica had been used by people involved in unsavory activities. He didn’t explain what he meant, only commenting that there were car tire marks leading into one of the trails, and that at the time, no one investigated because everyone was afraid.

These kinds of stories reappeared from time to time, always anonymous, always incomplete. Someone said there was a path where the grass grew differently, as if it had been trodden. Another swore they once saw a red shadow in the distance standing among stones. The person who told this was never found, and there was never any proof. But family members wrote everything down. Every whisper was recorded as if it were a piece of a puzzle. The problem is that over time, even pain begins to adapt to everyday life.

In 1999, Marisol’s parents moved to a more distant neighborhood in Shalapa. Living in the same place where their daughter woke up, where the phone rang on Sundays, where her red backpack hung on the door hanger, was already unbearable. The move was silent. They took only what fit in the car. The daughter’s photo remained in her mother’s wallet, still in the same place with a piece of yellow tape attached to the back as a reminder.

In 2001, Luis’s father fell ill. He spent most of his time at home, surrounded by old papers and maps. Shortly before his death, he said a sentence that Luis’s sister kept as a testament. They entered a place where no one had the courage to go, and there they remain, waiting. That feeling that there was something unseen, something hidden underground, began to torment the family more and more. But there were no longer any means to resume formal searches.

The mines remained abandoned. Some had buried entrances, others were known only to former workers who had long since passed away. The authorities never considered the possibility of excavating based on an old rumor, mainly because there was no proof that the couple had even passed through there. What was also lost over the years was collective interest. When new cases of disappearances arose, and continued to arise, primarily among young people in the central region of Veracruz, the case of Luis and Marisol was remembered only as a footnote, sometimes referred to by radio broadcasters as the story of that couple with the red backpack.

But no one else asked, no one investigated. Until, by chance, in 2005, a group of university students appeared in the region. They were architecture students from the Universidad Veracruzana, Orizaba Campus. They were documenting colonial structures, geological formations, and ruined spaces for a project on abandoned heritage. One of the young men had relatives in Songolica and suggested including the region’s mines. The idea was simple: photograph tunnels, take entrance measurements, and record images of rarely accessed underground spaces. With informal permission from a landowner, they entered a forgotten mine, one of the oldest, already half-buried, located on a hillside between Atlilco and the road that descends to Songolica.

The entrance was partially covered by stones and roots. According to one of the students’ later accounts, the interior was damp, with a smell of iron and old moss. They used flashlights and ropes to advance carefully. They didn’t expect to find anything but natural stones and columns. But what they saw at the end of that tunnel changed everything. To the right of a side gallery, they saw bones. At first, they thought they were animal bones, but as they got closer, they noticed their shape.

Ribs, skulls, femurs. They were leaning against the stone wall. Two human skeletons in a sitting position, chained together with what appeared to be rusty wire or remnants of metal rope. There was broken wood all around, scraps of fabric, and debris accumulated over time. The group left immediately, shaken, dirty, not knowing exactly what to do. That same day, they went to the Atla Wilco municipal police station. The story was recorded. In less than 48 hours, the mine was isolated by Civil Protection, and then, 11 years later, Luis and Marisol’s case was reopened, not by a court decision, not by the efforts of investigators, but because a group of curious young people decided to go down where no one else would.

When the experts from the State Attorney General’s Office arrived at the mine entrance, still in the first week of April 2005, the access path had already been partially trampled by curious onlookers in the region. Although the area was officially isolated, it was impossible to prevent the news from spreading. Human bones had been found in a forgotten mine in the Zongolica mountains. And even before the excavations began, many residents were certain who might be there.

But the technicians aren’t working with assumptions. They began by mapping the main gallery, taking topographical notes, and installing portable lighting poles for each meter of excavation. The first images captured with digital cameras showed the exact scene described by the students: two skeletons sitting against an uneven wall, partially covered by debris. Natural decomposition had taken its toll over time, but there were also signs of ancient ties on wrists and ankles made with what looked like improvised metal rope. Further back, about 8 meters away, were more remains.

Two additional skeletons, these lying laterally, were mixed with wood fragments, rotten sacks, and a half-buried black tarp. In total, four sets of bones were collected for analysis. None of them were complete. The forensic team, under the guidance of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, began the standard triage: bone collection, density analysis, measurements, and submission for genetic comparison. It would take days, perhaps weeks, before it was known whether any of the bodies could be identified. But it was during that procedure that something caught their attention.

A few meters from the first wall, where the two skeletons were leaning, one of the technicians tripped over something partially buried in the damp earth. It was a misshapen volume, covered in thick dust and mold. Pulling it open revealed a red backpack. The worn fabric shared a rusty, but still recognizable, clasp. On the side, attached to a broken strap, was a faded yellow ribbon, stuck as if someone had placed it there on purpose. A small detail, but for someone familiar with the story, it was impossible to ignore.

The backpack was carefully carried to the mobile laboratory set up at the mine entrance. Inside, the experts found scraps of paper, a dried lipstick, an old 500-peso coin, and something that made time stand still. A faded photograph, still partially legible, showed a man and a woman smiling, leaning against a red car, on a dirt road surrounded by green hills. The image was damp and disfigured, but the faces were still recognizable.

The next day, the photo was taken to Shalapa. When Marisol’s mother saw it, there was no doubt. Despite the wear and tear on the image, despite the Mo that covered the bottom edge, she recognized not only the two young men, but also the yellow ribbon she herself sewed onto her daughter’s backpack years before. That’s hers, that’s her backpack, and we took that photo before they left. The confirmation was emotional, but not technical.

The prosecution requested DNA testing for the four skeletons found. These tests would be compared with the genetic data already recorded in the closed 1994 case. However, weeks later, the result came as a further blow. None of the four bodies belonged to Luis or Marisol. This revelation caused a shock no one expected, because while it seemed to remove the couple from the crime scene, it also linked them to it in a disturbing way. If it wasn’t them, why was the backpack there?

How did that photo end up in that spot in the mine, abandoned for more than a decade? Had they been there and managed to escape? Or were they responsible for something that was never discovered? The Public Ministry reclassified the discovery as an incidental discovery related to a closed case. The mine, now considered a crime scene, was officially sealed, and the entire surrounding area was declared of criminal interest. But that didn’t bring any answers, only more questions. The families were called to testify again.

They were listened to with new recorders, updated cards, and digital forms. They were asked if they knew of any other objects the couple had brought. They were shown photos of the damaged belongings: the lipstick, the old coin, pieces of cloth. Not a single detail led to anything further. The final report established that the skeletons belonged to two men and two women, all young adults, who had died more than 10 years ago. No identification was possible, no names were assigned. And the question remained.

How many other people disappeared in the Songolica Mountains between the 1990s and early 2000s without anyone ever knowing? Meanwhile, the image of the two young men in front of the red car became a symbol of something much larger. It began circulating on old internet forums, on posters for events about disappearances, and on school murals in the region. The story of the red backpack with the yellow tape found in a closed mine became almost an urban legend.

But for the parents, it was just another torture, because if they weren’t dead, where were they? And if they were alive, why didn’t they ever return? The time between questions and silence began to stretch into years. Until today, no one responded. After the official announcement that none of the four skeletons found belonged to Luis Eduardo or Marisol, something very strange happened to the case. It seemed to vanish a second time, but in a crueler, more definitive way. The state of Veracruz at that time did not have sufficient forensic infrastructure to process all the findings of unidentified human remains.

In 2005, most of the nameless bodies ended up piled up in public refrigerators for months and then buried in mass graves with numerical labels. The four skeletons from the mine did not escape that fate. After months of analysis and unsuccessful attempts at genetic matching, they were declared unidentified individuals and quietly buried in a municipal cemetery in Zongólica. Marisol’s parents protested, calling it an insult. Her mother personally went to the Public Ministry and demanded the return of her backpack.

But he was informed that the object would become part of a permanent record of evidence, sealed for an indefinite period of time. When he asked for how long, no one could answer. Luis’s family did not grant further interviews. His sister, who had assumed responsibility for preserving the documents left by his father, stored them in a trunk and locked them in the house’s storage room. She said there was no point in continuing to search if even the remains found didn’t help clarify what happened.

But not everyone forgot. With the arrival of the internet to the region’s communities, online forums and blogs began to address the case more freely. Theories emerged in obscure places, raising hypotheses that the authorities never officially addressed. One claimed that the mine had been used by armed groups in the 1990s as a punishment site for deserters. Another claimed that for a brief period between 1993 and 1996, certain areas of the region served as clandestine corridors for arms trafficking between Veracruz and Oaxaca, and that any outsiders who crossed the wrong routes were simply eliminated.

But these theories, no matter how often they were repeated, were never supported by proof. They were based on what I’d been told, what I’d heard, and on disjointed memories. No one assumed anything, no one named names, and when asked directly, most residents preferred to change the subject. Meanwhile, the only real object, the only concrete evidence connecting Marisol to the mine—the red backpack with the yellow tape—remained locked in a safe at the Veracruz Public Ministry. The photo inside it, now digitized, became almost a piece of newspaper archives.

It was used in reports on missing persons, in debates about the precariousness of forensic investigations, and in conferences on collective memory. But rarely did anyone remember the names of the two young women in the image. Marisol’s mother, however, never stopped remembering. Two years after the discovery, she began doing something that frightened the neighbors. She would spend hours standing in front of her bedroom mirror with a replica of the backpack in her hands, rehearsing the moment her daughter would return.

She would say out loud phrases she imagined she would say, “My girl, you’re back.” I knew. I always waited for you. I did it with the door closed like a ritual. Her husband, who had barely spoken since the year of the discovery, preferred to go out and walk long distances aimlessly. Once, they found him on the road between Banderilla and Chico, disoriented. They said he was asking the drivers if they had seen a red car. The family’s lives began to revolve around her absence.

An absence that now had a concrete geographic location, but remained formless. The mine was finally sealed in late 2006 with industrial welding on the bars and federal property signs, access prohibited. No further investigation was conducted. The site was forgotten again. No major excavation, no new search for artifacts, nothing. And yet, in 2008, a reporter from Mexico City, curious about the case, decided to visit the region. He made a brief report for a television program where he showed images of the trail, the dense vegetation, and discussed the discovery of the remains and the backpack.

The story didn’t have much impact. The program aired late at night, but one specific detail caught the attention of a small group of former miners in the region who watched the segment and commented on something no one had noticed before. In the scene where the reporter walks with the camera through a clearing, there is a fallen metal structure, almost covered by tall grass. According to them, this wasn’t part of the mine where the bodies were found. It was the entrance to a secondary gallery never officially mapped, a smaller extension used in the 1970s only for ventilation and storage.

If true, it meant the mine hadn’t been fully explored. But when the relatives learned of this and tried to reopen the case, they were told there was no formal complaint filed regarding another tunnel. The Public Prosecutor’s Office refused to open a new investigation due to a lack of evidence. This created another layer of silence, because now, in addition to the absence of the bodies, there was also the feeling that something was still buried, but that no one else wanted to touch.

The bones found didn’t help. The backpack revealed little. The photograph brought only nostalgia, and the only certainty that remained was that in that immense, forgotten mountain range, perhaps there were other places where Luis and Marisol had been, places that no one else wanted to find. Meanwhile, the last image of the two continued to circulate on the internet. The dusty smile of a young couple in front of a car that was also never found. And behind them, the same green landscape that from the beginning hid more than it seemed to reveal.

Almost 14 years after their disappearance, in January 2008, Luis and Marisol’s story began circulating again among investigators in Veracruz for a completely trivial reason: a license plate. An administrative agent from the State Vehicle Registry found, in a batch of old scanned documents, the chassis number of a red 1991 Volkswagen Caribe, with incomplete information. The record indicated that the vehicle had been registered in the name of Luis Eduardo Ramírez Ávila until March 1994, with the last movement at a checkpoint in the southern part of the state.

But the curious detail is that the license plate number, which should have been listed as lost or inactive, was inexplicably linked to an active vehicle registered in northern Puebla. The news hit the family like a bombshell. At the time, Luis’s sister still had access to public attorneys through her work. She requested a broader investigation, and this time, for the first time in years, the response was immediate. A team from the Veracruz Ministerial Police was deployed to cooperate with Puebla authorities.

The location of the active vehicle was traced to a used car lot on the outskirts of Zacatlán. Upon arrival, officers found the car with the corresponding license plate. It was a Caribe, yes, red, but already completely modified. It had dull paint, replaced doors, altered headlights. The lot owner presented the documents. He had purchased the car in 2006 from an unknown customer who paid in cash. He said the vehicle had been parked since then, but a comparison of the engine and chassis numbers proved disappointing.

It wasn’t the same car. The error lay in a bureaucratic license plate change during a regularization process in 2004. The system had accidentally attributed Luis’s vehicle number to another car with similar characteristics. An administrative error, a failed crossing, nothing more. When the official report was delivered, Marisol’s mother cried in public for the first time. She cried with rage. In front of the press, she uttered a sentence that silenced everyone around her. It’s not just their absence anymore; now they’re also killing us with their mistakes.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office shielded itself. It declared that this was a historical error not attributable to the criminal investigation and that all reasonable efforts had been exhausted. The truth is that the case was returning to the same place as always: oblivion. Only this time the damage was greater because the false lead not only reopened old wounds but also destroyed what faith remained in institutional competence. And so the name of Luis Eduardo Ramírez returned to the archives.

Marisol Vargas too. But what no one expected was that in that same year, a figure from the past, a nearly forgotten name, would unexpectedly appear. It was Jacinto, the farmer who in 1994 had said he saw the couple in Tequila buying gasoline. Already elderly, now with mobility difficulties and a compromised lung, he was interviewed by anthropology students from Shalapa who were making a documentary about oral histories of the mountains. During the interview, Jacinto recounted the episode with a detail that had never been recorded in the records of the time.

He said that the morning he saw the young men, there was also another man in the country store, a stranger, a man with a different accent who seemed uncomfortable by the couple’s presence. He said the man paid for cigarettes, left before them, but stared at the two of them as if he were observing them. I didn’t like the look on his face, but no one asked me about it at the time. That detail, even without a name, without a precise physical description, rekindled a doubt.

What if the disappearance wasn’t an accident? What if there was a third party involved? Someone who perhaps followed the couple, saw them enter the trail toward the waterfall, or approached them along the way? The information reached the hands of a Shalapa community member who, despite the case being closed, became sympathetic. She ordered a re-evaluation of the 1994 testimonies, but time had erased almost everything. Jacinto couldn’t remember any more names.

The original records were illegible. The notes from the tequila delegation had been discarded in administrative reforms. Once again, the trail was disappearing, but this time the feeling was different, as if after so many years what was preventing the case from being solved was no longer the absence of clues, but the excess of them. Too much information without connections, disjointed, like a puzzle in which all the pieces are of different images. Marisol’s mother began repeating a phrase that tormented the few who still visited her.

I think someone did tell us the truth, but we just didn’t know how to recognize it because deep down, there was an intuition that the answer lay somewhere, but that perhaps no one else had the strength or the time to find it. And so, even with the faded photo still circulating on missing persons networks and the red backpack sealed as official evidence, Luis and Marisol’s disappearance returned to its place of origin, to the void. That same void that began on a dirt road in the shadow of the Songolica Mountains, where everything seemed too peaceful to hide so much pain.

In the decade following the final dismissal of the case, something curious began to happen around Shalapa, Orizaba, and in the scattered villages of the Zongolica Mountains. The names Luis and Marisol began to quietly disappear from school records, birth certificates, and honor rolls. It wasn’t that they were prohibited—there was no explicit order—but no one else was baptizing their children with those names. Not there, not at that time.

It seemed like a form of respect or fear, as if repeating the names of the disappeared risked awakening something that silence was trying to protect. The oldest neighbors still remembered. Luis’s sister’s house had a tabletop radio that he used to repair on weekends. The device stopped working in 1995, but no one had the courage to throw it away. It remained on the living room mantel as a reminder.

In Marisol’s parents’ house, the red backpack earned a place of its own. No longer on the door hanger, but on a makeshift altar with paper flowers, candles, and old photographs. The once vibrant yellow ribbon now looked like part of a locket, worn but protected by glass. Once a year, at the beginning of April, the mother would still light a candle and say softly, “You haven’t come back yet, but I’m still waiting for you.” Luis and Marisol’s disappearance began to be counted as a warning.

Teachers mentioned the case in conversations with adolescent students, especially those who liked to venture off the beaten path and into isolated regions. “Never go into places you don’t know without telling them where you’re going,” they said. Don’t forget what happened to the Shalapa residents. But little by little, the story lost its real details and took on the appearance of a local fable. Some said their car was seen years later in another state. Others said they were mistaken for criminals.

Some claimed they had fled together to start a new life. And among the younger generations, fantastic stories even emerged, as if the mine where the bones were found was cursed. None of these versions matched the documents, the original accounts, or the truth told by those families. Meanwhile, Luis’s siblings and cousins grew up, started families, and moved to other cities. His sister, who inherited the Father’s research belongings, kept everything in an attic. She never threw them away, never read them completely.

“When someone really wants to know, the folders are there,” he said. But no one else asked. The mountain community also changed. Access to the once-abandoned trails was restricted by new fences and private property. The old mines were sold to companies planning rural tourism, but nothing ever came of it. The mine where the four skeletons were found was officially forgotten. No plaque, no tribute, no sign. In 2012, a school group from Atla Wilco proposed creating a memory project featuring local stories of disappearances.

The case of Luis and Marisol was chosen as the central theme. One of the students involved was the grandson of one of the volunteers who searched for the couple in 1994. Upon reading the files, he wrote something that remained engraved on the school wall for two years. We didn’t know we could disappear. They taught us that. That simple phrase became a symbol of collective grief, not only for Luis and Marisol, but for all the others who disappeared without answer, along dirt roads, in the mountains, in areas where no one else wanted to look.

The Public Ministry never reopened the case. The backpack remained in the evidence box until at least 2014, when a judicial reorganization moved hundreds of old items to off-site storage. No one was able to report the object’s final destination. The promoter, who had been moved by Jacinto’s story, retired shortly after. No new promoter took on the case, but in some homes in Shalapa, their names still resonated. A childhood neighbor of Luis, who years later became an interstate bus driver, said that whenever he crossed the highway between Orizaba and Songolica, he looked toward the tall weeds and thought, “They’re still there.”

No one saw them, but they see us.” The case stopped being an investigation. It became a presence at the Sunday fair, at the market, at the church. There was always someone who still remembered Marisol’s expression in the photograph, Luis’s plaid shirt, the way they laughed, not because they were famous, but because they were possible, because they could have been anyone. And when the younger ones asked why no one knew what really happened, the older ones would just say, “Because no one wanted to go where they went.” In 2015, 21 years after

Following the disappearance of Luis Eduardo and Marisol, a woman named Ángela, Marisol’s cousin on her mother’s side, decided to take on a task the family could no longer bear: sorting through everything. She was 36 years old at the time. She was a history teacher at a public school and had always grown up listening to the family’s interrupted conversations during meals. She wasn’t close to Marisol as a child, but she admired her. She remembered her aunt’s stories, her cousin’s patience with the children, and especially that red backpack she wore on weekends.

For Ángela, Marisol had become an almost mythical figure, not because of her death, but because of the complete lack of answers. And that was unbearable for someone who studied archives every day. Through painstaking and bureaucratic efforts, she obtained copies of the original case documents. Some of them were on microfilms forgotten in the prosecutor’s office’s dead archive; others were in physical folders with erased labels stored in the old Orizaba courtroom. It took her weeks to put together a coherent timeline because the documents were incomplete, with unexplained gaps, changed names, and inverted dates.

But she persisted. Throughout that year, Ángela retraced the journeys described in the 1994 testimonies. Alone, by bus, motorcycle, and whenever possible, on foot. She passed through Tequila, Atlahilco, and the outlying areas of Songólica. She spoke with children of former residents. She went to churches where masses were being said for the disappeared and tried to retrace the path to the waterfall mentioned by Jacinto, the farmer who last saw them. The path, however, no longer existed. It was covered by an irregular coffee plantation, surrounded by makeshift fences and a privately maintained power tower.

Angela asked the oldest residents if they remembered any accidents there, or if there had been any noises, stories, anything that might indicate what might have happened that April morning in 1994. Most shook their heads. They said it was better to forget, that those were just things from the bad times. One man, however, agreed to talk. In a weak voice, he said only one sentence. If they got lost, it was because someone wanted them to get lost. And he fell. Back in Shalapa, Angela organized everything into her own file.

Copies, photos, newspaper clippings, mine maps, transcripts of stories. She sent one copy to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, another to an NGO specializing in forced disappearances, and kept the original at home. But again, nothing came of it. She insisted on trying to contact the last active sponsor still connected with the case. He received her formally, but without enthusiasm. He said that with the passage of time, any new investigation would depend on high-impact elements, such as a new body, a direct witness, or concrete evidence.

Angela asked if the backpack wasn’t useful. He replied, “An old backpack doesn’t prove anything, miss.” And he ended the meeting. Still, he didn’t give up. He published a blog in his cousin’s name, with an illustrated timeline and images of the tests. He got small pieces on local radio and a mention on an independent YouTube show. But as always, time devoured the interest. Most of the views came from outside the country.

Inside, almost no one else clicked. Around the same time, Luis’s sister, who was already over 50, fell ill. Advanced cancer prevented her from following what Angela was doing. When she died in 2017, her children opened the attic where their father kept the old search files. There were the original trail maps, letters from residents, and tapes of interviews recorded in 1994. Everything intact, everything stored with the care of someone who believed they would one day make sense.

Angela was called in to decide what to do with the material. She brought everything, digitized it, cataloged it, and added it to the file. And then something curious happened. By cross-referencing data from old maps with current rural property documents, she discovered that the area where the mine was located, where the bones were found in 2005, had been sold. A local landowner transferred it to an alternative energy production company in 2011. The company, in turn, never built anything there; it only kept the deed in its name and fenced the area with private property signs, restricting access.

Angela tried to contact them, but never received a response. She sent letters, emails, formal requests. No response, no authorization to enter the site. A lawyer friend suggested trying legal proceedings. But the cost of the process was unfeasible. And even if she gained access, who would finance a new excavation? On what basis? And that’s when Angela understood. Time doesn’t just cover up traces; it also covers up willpower, resources, and drive. It wasn’t enough to know where to look. It was necessary to have someone willing to search, and that no longer existed.

In 2019, she wrote her last blog post. I reviewed every document, spoke to every person, went where no one wanted to return, but there was no response, and I don’t know if there ever will be. The post had 42 views, no comments, and so the case of Luis Eduardo and Marisol returned to where it always was, in the space between the last revealed image and the silence that followed. Only now, even those who tried last were also tired. In 2020, the world changed, and with it, so did the pace of everything: investigations, priorities, travel.

But in the homes of Shalapa, where Marisol’s name was still spoken with care and where Luis’s old papers remained folded in boxes, time had already stopped many years before. The pandemic forced everyone into a kind of silence. A new silence, but one that was already all too familiar to the families of the disappeared. “We have been in emotional confinement for decades,” Ángela said in a remote interview conducted by a small group of documentary filmmakers from the north of the country.

They were preparing a project on unsolved disappearances and happened upon Marisol’s archived blog. They invited Angela to tell the story. She hesitated. She didn’t want to repeat everything again, but she ended up accepting. She spoke for two hours, explaining the documents, showing maps, talking about the backpack and the photograph. When the recording ended, one of the interviewers, a 23-year-old man, remained silent for a few seconds and said, “I was born the year they disappeared.

It’s as if they’d always been absent. The phrase echoed in Angela’s head for days. Because that’s what it was. For most of the people who lived there now, Luis and Marisol never really existed. They were just part of a story that circulated with less force each year, like a curve in the road where something happened or an abandoned mine with a dark past. In Atlahüilco, the path that would have once led to the site of the supposed waterfall was completely swallowed up by fences and tall weeds.

The mine entrance was covered with dirt and a layer of uneven concrete after an access renovation promoted by the company that owns it. There’s no plaque, no notice, just a small depression in the hillside where vegetation doesn’t grow well, perhaps due to roots that were forcibly uprooted. In Tequila, the store where Jacinto said he saw the couple was transformed into a small agricultural materials warehouse. The facade was repainted, and no one else clearly remembers the 1990s.

Jacinto died in 2018 without any new names being revealed, without having been formally heard again. And the documents, the files, are scattered. Some were destroyed in floods, some filed under codes that no one else knows how to decipher. The backpack report, lost among boxes at the prosecutor’s office. The photograph, digitally stored in a police database under the number of a closed case. No one sees it, no one searches for it. So what remains? Perhaps only what could never be touched: the impact.

Because even without names, without recognition, without final truth, the disappearance of Luis and Marisol left a deep mark, not only on their families, but also on the very way the community came to view certain places. There was a time when young people went to the mountains with lightheartedness. They sought waterfalls, caves, horizons. After 1994, that changed. The region began to carry a kind of shadow. It wasn’t an open fear, it was a concern, a weight, as if something had happened there that was never resolved and that therefore remained pending.

Angela never returned to the trail. She said she did everything she could, that she had nothing left to do, but she did one thing in secret. She had the photo of Luis and Marisol printed on new paper, digitally restored by a friend. She had it framed. And one afternoon, without warning, she went to Marisol’s mother’s house and delivered it. The elderly woman was slow to recognize the image. Her eyes were dull, her memory intermittent, but when she touched the frame, she smiled.

That was the one from before they left. They placed the photo on the mantelpiece. Next to it, a small candle and a vase of dried flowers. It was the final gesture. Not as closure, because there is no way to close what was never understood, but as a sign that at least someone still kept track, someone still remembered. And so the story of Luis Eduardo Ramírez Ávila and Marisol Vargas Gallardo continued to exist. Not in the archives, not in the reports, but in the space between a path no one else travels and the silence of a mine no one else opened.

Over time, when the documents are worn out, the main voices have fallen silent, and the evidence has been lost, all that remains are hypotheses. Some stem from what was said at the time, others from what was left unsaid, but all are attempts to organize the chaos into something bearable. In the case of Luis and Marisol, three theories have spread over the years. None have been confirmed, none have been completely dismissed. The mistake of the route and the hidden tragedy.

This is the version most widely accepted by the initial investigators. According to it, the couple had in fact taken the wrong path indicated by Jacinto toward a waterfall that never existed. The road, almost abandoned in the 1990s, ended in an area used decades earlier as a staging post for mineral extraction. They entered by car, perhaps seeking a higher place to take photos, perhaps just to explore. The terrain was unstable. A slight slip, a miscalculated curve, or a mechanical failure would be enough for the car to skid and fall into one of the ancient galleries covered by foliage.

Since official searches avoided mines due to the risk of collapse, and private searches were conducted only in accessible areas, the exact crash site was never discovered. This hypothesis would explain the complete disappearance of the car and the bodies. It would also explain why no objects were found, except for the backpack, possibly thrown out upon impact or removed by someone who mistakenly took it to another mine years later. The problem with this theory is that it requires a cruel coincidence of factors: no one heard the accident, no skid marks were noticed, and the bodies and the car remained completely invisible to all official and voluntary searches.

Human interference. This is the most painful hypothesis, and also the one most feared by the families. That the couple was intercepted by someone along the way. Perhaps the same man mentioned by Jacinto, who was watching them at the gas station. In this version, they would have been mistaken for someone else or simply an easy target in an isolated area. The mine where the remains were found in 2005 would have been used not as a hiding place, but as a disposal site.

The backpack found with the photo could be a piece that escaped an attempt to hide it or a trace left by mistake. This would explain why there were four unidentified skeletons at the scene. If Luis and Marisol were involved, the other two bodies could be those of third parties connected to the crime. If they weren’t, they could have simply witnessed something they shouldn’t have. And they were silenced. But this hypothesis also has flaws. The bones belonged to them. No trace of violence was found on the outer perimeter.

And perhaps more importantly, no one in that region had a known history of similar crimes, at least not officially recorded. The escape, less credible, but still echoed by some. Luis and Marisol decided to disappear of their own volition. Some say their relationship was more conflicted than it seemed. Others speak of family pressure, of fear of something that was never mentioned. The absence of traces would be part of the plan. They improvised the trip to deceive, abandoned the car in a remote location, and disappeared under a new identity.

The backpack was allegedly planted or simply forgotten. The photograph is based on a memory that a third party found and never understood its meaning. But this hypothesis never held true. Nothing in Luis’s or Marisol’s profiles indicated any intention to flee. They had stable employment, strong family ties, no debt, no history of conflict, and most importantly, there was no bank transaction, no use of documents, or subsequent appearance anywhere. If it was an escape, it was too perfect, too silent, too impossible.

Ultimately, what these hypotheses reveal is something deeper than simple doubt. It is the abyss of the absolute absence of certainty, because each of these versions demands the acceptance of a double loss: that of the bodies and that of the narrative. And perhaps that is why, even after so many years, what weighs most is not the tragedy, but the not knowing. In the absence of truth, each person constructs their own.

Marisol’s mother, already elderly, chose to believe the first hypothesis, that the two died together in a place no one found, that it was quick, without pain. They died with love, she once said, her voice breaking. Luis’s sister, before dying, said the opposite, that someone killed them, that there was malice, that there was a complicit silence. Ángela, for her part, never chose. I don’t know what happened, she said, but something did happen, and that should be enough to remind them not to forget.

And perhaps that’s the point. Perhaps it’s not about finding an ending, but about understanding that some stories were never meant to end, that there are absences that don’t ask for answers, only memory. More than 30 years have passed since that weekend in the Songolica mountains. Almost no one speaks directly about Luis and Marisol. Not out of disrespect, but because time creates a new way of remembering, a memory that doesn’t require words, a memory that imposes itself through spaces.

In Shalapa, the neighborhood where Marisol lived changed completely. The street where she grew up was paved. The old houses gave way to low-rise buildings. But a tree planted by her father when she was still a child still stands. Its shadow covers part of the sidewalk where the red backpack passed every Friday morning. The oldest neighbor, Doña Josefina, always says that tree is hers, that the day they cut it down, the neighborhood will feel it. Nothing has changed in the house where Luis lived with his parents.

His sister kept everything until the end: the furniture, the picture frames, even the small box of radio parts he repaired on weekends. When she died, the nephews considered renting the house, but upon moving in, none of them could move a single object. They closed the door and left it as it was. Today, the house remains closed, like an invisible museum of a history no one else wants to change. In the school where Marisol taught, there is still an old attendance book with her signature.

The handwriting is firm, slanted, with small ribbons. A cleaning lady keeps the notebook hidden in a closet. She says it’s a reminder of what shouldn’t be forgotten, but perhaps the quietest gesture occurred far away, in the mountains where it all began. In 2023, a group of young environmentalists from the region proposed cleaning old trails in the Songolica Mountains. The idea was to reopen historic paths, preserve springs, and identify environmental risk points. During their work, they came across a hillside covered in tall weeds, near the old mine that had been sealed with concrete years before.

There, among rocks and roots, they found a piece of corroded metal, what appeared to be part of an old bumper with traces of red paint. There was no chassis number, no clear marking, but the piece was there, partially buried in a location not listed on any accident map. They didn’t know the story. They took photos, noted the coordinates, and posted them on social media as part of an environmental survey. The post reached Ángela by chance, sent by a former student who was still following the archived blog.

She saw the image and recognized the tone, the curvature, the detail of the body. It could be from any car, her friends told her. But it could also be from just one. She didn’t share it publicly; she just saved the image, printed it, put it in a new folder, and wrote the last possibility on the back. Today, no one is officially searching for Luis Eduardo and Marisol, but there are still traces of them in all the places they passed, in the name that was no longer given to children, in the backpack that no one wanted to throw away, in the road that

It was never traveled in the same way again, and in the faded photograph that now lives on at least four houses away, printed, pasted, stored, because what remained wasn’t the crime, nor the scandal, nor the tragedy. What remained was the absence, an absence so profound that it came to shape even what is said in whispers, even what is no longer said. And sometimes that’s enough for a name to never truly disappear. When a story drags on for three decades without an answer, it ceases to be just a case.

It becomes an echo, a constant sound that crosses generations. This is what happened with the disappearance of Luis Eduardo Ramírez Ávila and Marisol Vargas Gallardo. What is most striking as the years pass is not the brutality of the disappearance, but its precision. It was as if someone had erased the two from the map, from official memory, from the investigation, leaving no room even for doubt, only silence. The car, the most visible trace of all possible, was never found.

Not in the forest, not in the mines, not sold with another chassis, not dismantled, not burned, nothing. The bodies, if they exist, remain underground somewhere where no one else wants to look, or perhaps they are no longer there at all. The backpack, despite being the most concrete object in the narrative, remains unused as evidence, stored away, ignored. The only thing it revealed was the photograph, that single moment when the two were still whole, clean, alive.

The simplest, most innocent, and also the cruelest image, because everything we know about them, everything we managed to recover, ends exactly there. And the rest, the rest, is what each of us decided to imagine. Some said they were murdered and buried far away. Others believe they died in an accident hidden by the mountains. There are those who swear they saw the car in another state, that they heard someone with a similar accent, that they dreamed of a girl who looked like Marisol, but nothing, absolutely nothing, was ever confirmed.

Today, the case is considered closed due to a lack of investigative evidence, but in practice, it was never truly investigated to the end. Luis and Marisol remain as they were since April 1994: absent. Only now, they are not remembered only by their families. They have become part of a collective memory that no one can quite name, but which is there in the details, in the caution when taking the road, in the fear of straying too far from the route, in the story told in a low voice when someone wants to explain what it means to disappear in Mexico.

They were just two young people, a telecommunications technician, a preschool teacher. They weren’t involved in anything, they weren’t looking for danger, they just wanted a weekend of silence and scenery, and for some reason, still unknown, they never returned. And perhaps that’s the cruelest point. It wasn’t the crime, it wasn’t the pain, it was the fact that even after everything, no one ever knew what happened. And when the truth doesn’t emerge, what remains is fear. A fear that over the years turned into respect and then into silence. And today it’s only absence. Amen.

News

Little Girl Said: “My Father Had That Same Tattoo” — 5 Bikers Froze When They Realized What It Meant

The chrome catches sunlight like a mirror to the past. Ten Harley Davidsons sit parked outside Rusty’s Diner, engines ticking…

My Husband Left Me for a Fitter Woman Because He Said I Was “Too Big.” When He Came Back to Pick Up His Things… He Found a Note That Changed Everything.

When Mark left Emily just two months ago, there were no tears, no apologies, not even a hint of doubt…

The Maid Begged Her to Stop — But What the MILLIONAIRE’S Fiancée Did to the BABY Left Everyone…

The Broken Sound of Silence —Please, ma’am— Grace whispered, her voice cracking mid-sentence. —He’s just a baby. Cassandra didn’t stop….

My Husband Slapped Me in Front of His Mother, Who Simply Sat with an Arrogant Smile — But Our Ten-Year-Old Son Jumped Up, and What He Did Next Made Them Regret Ever Touching Me. It Was a Moment They Would Never Forget…

The slap came so fast I barely had time to blink. The sound cracked around the dining room like a…

I never planned to ruin my own wedding. But the moment I heard his mother scoff, saying: ‘People like you don’t belong here,’ something inside me broke. I threw my bouquet to the ground, tore off my veil, and took my mother’s hand. Gasps erupted behind us as I walked away from a million-dollar ceremony… and perhaps from him, too. But tell me: would you have stayed?

My name is Emily Parker , and the day I was supposed to marry Ethan began like a perfect California dream. The…

I Invited My Son and His Wife Over for Christmas Dinner. I Surprised Him with a BMW and Gifted Her a Designer Bag. Then My Son Smirked Arrogantly and Said: “Mom, My Wife Told Me I Need to Teach You a Lesson. There Will Be No Gifts for You.” My Daughter-in-Law Sat Smiling at My Humiliation. I Slowly Took Out an Envelope and Said: “Perfect. Then I Have One More Gift for the Two of You.” As Soon as He Opened It, His Hands Began to Tremble…

On the morning of December 24th, Elena Müller, a retired German accountant who had lived in Valencia for years, woke…

End of content

No more pages to load