June 1944. The claustrophobic green hell of the Normandy bokeh. An 8 oz strand of simple telephone wire is about to paralyze 56 tons of German steel. This isn’t fiction. This isn’t a Hollywood script. This is the declassified almost unbelievable story of how one engineer’s desperate absurd idea halted the most feared weapon of the Second World War in less than 3 seconds.

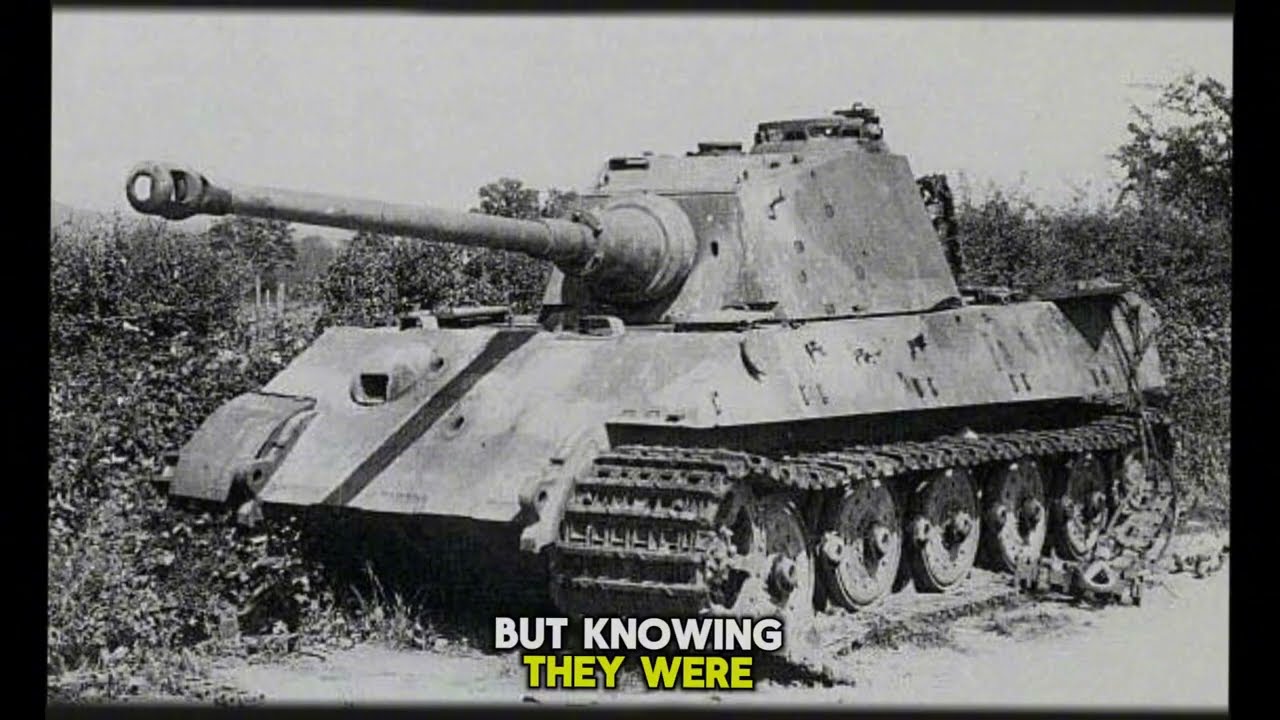

To understand how this happened, you first have to understand the monster. You have to understand the tiger. The panzer campvagen 66 tiger e even its name was an act of psychological warfare. When the tiger I first appeared, it shattered allied and Soviet confidence. It was not a tank. It was a fortress.

A 56-tonon predator designed for a single purpose to dominate. Its development began in 1941. Born from the shock of encountering the Soviet T34 and KV1 German engineers at Henchel and Porsche were ordered to create a heavy tank that was untouchable. And they succeeded. When production began in August 1942, it was the single most sophisticated and lethal ground weapon on Earth. Let’s talk about the armor.

The front of the hull was 100 mm of solid face hardened steel. The turret front 120 mm. Its side armor was 80 mm thick. To an American Sherman crew, these numbers were a death sentence. The Sherman’s standard 75mm gun could not penetrate the Tiger’s frontal armor at any range. Not at 1,000 m, not at 500 m, not at point blank range. Every round would simply bounce.

Allied crews developed a terrifying mathematics of survival. It was estimated that to guarantee a single Tiger kill, you had to be willing to lose five Shermans. Five. Think about that. Think about being the crew in the first, second, third, or fourth tank, knowing your job was simply to die so that the fifth tank might get a lucky shot into the Tiger’s thinner rear armor. Allied tankers called engaging a Tiger at range a suicide mission.

They were ordered to avoid it at all costs, to run, to hide, to call for air support that might never come. This created a Tiger phobia that crippled entire divisions. And then there was the gun. The Tiger was built around the legendary 88 mm KWK36 cannon. This wasn’t just a tank gun.

It was a modified version of the dreaded Flak 88 anti-aircraft gun, already famous for tearing Allied bombers from the sky and annihilating British tanks in North Africa. Mounted in the Tiger, it was a sniper rifle. It could punch through 4 in of sloped armor at 1,000 m. A Sherman’s frontal armor, it could penetrate that from 2,000 m away.

That’s over a mile. The Tiger crew could stop, spot an Allied column, and destroy five Shermans before the Americans even knew they were in range. The Tiger was safe. The Allies were helpless. Each Tiger was a masterpiece of lethal engineering. Each one cost over 650,000 Reichs marks.

Each one demanded 300,000 man-hour to build. Germany couldn’t afford to lose them. The Allies couldn’t afford to face them. The tank was powered by a Maybach HL230 P45 5P12 engine generating 700 horsepower. It could rotate its massive turret a full 360° in under a minute. It could climb a 35° slope. It could ford rivers 4 ft deep. It was in every sense invincible.

Or was it? Every legend has a secret. Every monster has a vulnerability. And the Tigers was beautiful. The Germans called it the Laf, the running gear. Look at a picture of a Sherman tank. You see simple vertical wheels, easy to build, easy to replace. Now look at a Tiger. It’s different.

It’s a complex interled overlapping system of road wheels. Nine road wheels per side, overlapping in three distinct rows. This wasn’t an accident. It was a deliberate, brilliant piece of German engineering. Why do this weight distribution? To stop the 56-tonon tank from sinking into soft ground, the engineers needed to distribute that immense weight over the widest possible track area. The overlapping pattern distributed the stress perfectly.

It gave the Tiger a ground pressure of just 14.8 8 lb per square in, lower than many lighter tanks, including the Sherman. This meant the Tiger could traverse soft, muddy ground that would bog down simpler designs. It also gave the crew an incredibly smooth ride, which improved gun accuracy while moving.

In theory, it was perfect in the field. It was a maintenance nightmare. This exquisite complexity was the Tiger’s Achilles heel. Think about those overlapping wheels. What happens when the tank drives through mud? The mud gets trapped. On the eastern front, Tiger crews faced a daily hell.

The gaps between the wheels would fill with thick Russian mud, which would then freeze solid overnight. The tracks would be locked, the tank completely immobilized. Crews spent hours every single morning under threat of sniper fire, desperately trying to chip frozen blocks of earth from the running gear with crowbars and blowtorrches. In the desert, it was sand.

The grit would grind down the rubber tire rings that cushioned each wheel, shattering the suspension. And then there was the repair. To change a single inner road wheel on a Tiger, a crew had to first remove up to eight of the outer wheels. What took a Sherman crew 20 minutes with basic tools took a Tiger crew half a day if they had a specialized heavy crane nearby.

This complexity had catastrophic costs. More friction, more points of failure, more opportunities for debris to lodge in the mechanism. It was a system designed for a perfect world, not for the blood and mud of a total war. And 4 days after landing on Omaha Beach, a 23-year-old electrician from Pittsburgh noticed his name was Corporal James Mallister. He was not an armor expert.

He was a combat engineer with the First Infantry Division. His unit had been tasked with clearing roadblocks outside the shattered town of Margals. And there he saw it, a tiger eye abandoned, its engine dead from fuel starvation. Mallister had seen a tiger exactly once. He climbed onto the cold hull. He touched the armor. He studied the tracks. He counted the wheels.

He measured the gaps with his hands. He noticed what the tank’s designers, in their quest for perfection, had overlooked. The overlapping wheels created narrow channels between their edges, tight vertical spaces where the wheels nearly touched, but didn’t. Each gap was perhaps 3 in wide, just enough for the wheels to rotate, but just narrow enough to trap objects of a certain dimension. He saw evidence.

A single stone wedged between two wheels had cracked the rubber tire on one of them. A piece of chain caught in the drive sprocket, had torn three track links before the crew managed to cut it free. Mallister, the electrician, understood systems. He understood tension. He ran his fingers along the massive track assembly. Each link weighed 11 lb.

The entire track assembly on one side weighed nearly 2,000 lb. Once that mass was moving, it generated enormous momentum. It resisted stopping, but Mallister realized if something did jam that mechanism, that same unstoppable momentum would amplify the damage. It would tear the machine apart from the inside before the driver could even react.

He filed the observation away. A curiosity, a footnote in a long, brutal day. 3 weeks later, his company was dug in along a hedge south of Carantan. and his curiosity. Sudinate was about to become the only thing standing between 32 men and annihilation. The terrain was the bokehage, the hedge of Normandy, older than the war, older than nations. They were not bushes.

They were massive earth and stone bms 4t high, topped with ancient thorny brambles. They divided the countryside into a claustrophobic maze. Each field was a fortress. Each gap in the hedge a killing ground. The bokeage turned the war of rapid maneuver into a grinding, brutal attrition. Infantry advanced by the meter.

Tanks became blind, their guns unable to traverse. The Americans had trained for open fields. They had trained for beach assaults. They had not trained for this. The hedgeros negated every Allied advantage. Armor couldn’t move. Air support couldn’t see targets through the thick canopy.

But the Germans, the Germans understood this terrain. They had four years to prepare. Every crossroads was pre-registered for mortar fire. Every gap was covered by interlocking MG42 machine guns. The Germans didn’t need to win. They just needed to delay. Every day the Allies spent bleeding in the Bokeage was another day to reinforce the interior, another day to move the Panzer divisions, another day to fortify the roads to St.

Listister’s platoon had been on the line for 18 days. They had advanced 2 miles. They had lost 11 men. The replacements were green. Farm boys from Iowa and factory workers from Detroit. They didn’t know the sound of a German mortar. They froze when the machine guns opened up.

Mallister and the other veterans taught them, “Dig deeper. Stay lower. Move faster.” Most learned. Some didn’t live long enough. June 28th, 0530 hours. The Germans counteratt attacked. Not a probe, not a patrol. A full strength armored thrust. Panzer grenaders, halftracks, and rolling at the spearhead. Four Tiger tanks from the 101st Heavy Panzer Battalion.

Intelligence had warned they were in the sector, but knowing they were present, and facing them were two very different experiences. The intel reports didn’t convey the sound, Mallister heard them before he saw them. The deep guttural growl of the Maybach engines, the metallic clank of tracks on cobblestone. The ground itself trembled.

His platoon was dug in along a sunken road running perpendicular to the German advance. 32 men, two bazookas, three Springfield rifles per foxhole. The orders were simple. Hold until relieved or overrun. No one expected them to stop four Tigers. The mission was to delay. To buy time for artillery, to force the Germans to deploy.

If the platoon held for 30 minutes, it would be a success. Survival was optional durix 615 hours. The Tigers appeared. Four gray monstrous shapes emerging from the morning mist. Their turrets traversed slowly. Their long 88 mm guns were elevated, ready to fire high explosive rounds into the hedge. They were coming and nothing on earth could stop them. The lead tank was 200 m out when it fired.

The shell hit a farmhouse to Mallister’s left. Stone and timber exploded into fragments. The concussion knocked dust from the hedge. The second Tiger fired, then the third. This was suppressive fire. It was designed to keep American heads down while the German infantry advanced beside them. The sound was distinctive.

The 88 mm KB236 gun had a flat, sharp, cracking report. It wasn’t the booming roar of American artillery. It was something harder, more percussive. Each shot was followed by the whistle of the shell in flight, then the crack of impact. They were firing high explosive rounds, not armor-piercing. The Tigers weren’t hunting tanks. They were clearing infantry. They didn’t even consider Mallister’s platoon a threat. They considered it a nuisance.

The tactics were methodical. Shell the hedro. Advance 50 m. Shall again let their infantry sweep the position. Move to the next objective. It was a meat grinder. Mallister looked at the two bazooka teams huddled in their foxholes. They were the platoon’s only anti-tank defense, and they were useless. Mallister knew the math.

The M1 Bazooka could, under ideal conditions, penetrate 3 in of armor. The effective range was 100 m. Beyond that, the shaped charge rocket’s accuracy was terrible. The Tiger’s frontal armor was 4 in thick, hardened, angled. Even a perfect hit at point blank range would likely just bounce off or shatter, alerting the crew to your exact location. The only vulnerable points were the engine deck and the lower rear hull.

To hit those, you had to let the 56-tonon monster pass you. You had to let it roll over your position, then rise up behind it and fire at a machine designed to kill you. None of Malister’s men were going to get that chance. The Tigers would shell the hedge to rubble. Then their machine guns would finish off any survivors. It was standard doctrine.

It was proven tactics. The Germans had done it a thousand times in Russia against troops more experienced than this American platoon. They do it here and it would work. Mallister looked at the sunken road. It was 15 ft wide, hardpacked dirt with ruts from farm carts.

It was the only route through this section of Boage that could support a tiger’s weight. The hedge on either side were too dense, the earth too soft. Engineers had checked 3 days earlier. Anything heavier than a halftrack would bog down within 20 ft. The tanks had to come down this road, single file, at walking speed, blind to their flanks.

This was where the platoon was supposed to make its stand. Two bazookas positioned to fire on the engine decks as the Tigers passed. Infantry with grenades to try and attack the vision ports. It was a forlorn hope. Desperation tactics. Mallister had watched crews train with the bazooka. It was a good weapon against the side of a panzer 4. It was marginal against a panther. It was suicide against a tiger.

He looked at his hands. He was still holding the coil of communications wire. 300 ft of braided steel cable. Standard field telephone wire 1/8 of an inch thick. Tensil strength rated for 200 lb. Nowhere near strong enough to stop a tank.

You could wrap it around a Tiger’s gun barrel and the tank wouldn’t even notice. You could drape it across the hull and the crew would brush it off. Wire was for communications, not for combat, but that wasn’t what he needed it to do. He remembered the abandoned Tiger, the cold steel, the gaps between the wheels, the cracked rubber from a single jammed stone, the 2,000lb track assembly, the momentum.

The idea was absurd. a single strand of wire against 56 tons of armor. It violated every principle of anti-tank warfare. Mines worked through explosive force. Bazookas worked through shaped charge penetration. Artillery worked through kinetic energy and over pressure. Wire had none of these. It was a nuisance, a delay, something to be brushed aside.

But wire could jam. That was the theory. If the wire caught in those overlapping wheels, if the angle was right, if the tension held, it might just jam the mechanism. Lock the track, immobilize the tank. It was a slim chance, an impossible chance, but the alternative was watching four Tigers roll through the platoon’s position and kill everyone in the hedge row.

The alternative was certain death. Mallister ran. He sprinted 50 meters down the sunken road, staying low in the depression where the tiger gunners couldn’t see him. The road curved slightly, creating a blind spot. He found what he needed. Two stout fence posts on opposite sides of the road. Weathered oak driven deep for a gate that no longer existed.

The posts were solid. Solid enough. He tied one end of the wire to the left post. He wrapped it three times around. He used a triple fisherman’s knot, something his father had taught him for securing electrical conduit, a knot that wouldn’t slip under load. He pulled the wire across the road.

He kept it taut, ankle height, maybe 8 in off the ground, low enough to catch the tiger’s running gear, high enough not to drag in the dirt. He tied the other end to the right post. Same technique, three wraps, maximum tension. The wire was taut enough to hum when he plucked it. It was almost invisible in the early morning shadow of the hedge.

He had 90 seconds before the lead tiger reached his position. Mallister scrambled back to his foxhole. He told no one. There was no time to explain. There was no certainty it would work. He just waited. The lead tiger entered the sunken road at 0620. It moved at walking speed, 4 km an hour. The engine was throttled down to reduce fuel consumption.

The commander’s hatch was open. An officer in a black Panzer uniform stood half exposed, scanning for threats. This was standard operating procedure in close terrain. The closed hatches reduced visibility to dangerous levels. Better to risk small arms fire than blunder into an ambush. The main gun was traversed left, covering the hedgero where Mallister’s platoon was hidden.

The coaxial machine gun was manned, ready to rake the treeine. The tank was 20 m from the wire. Meters. Mallister held his breath. The front left drive sprocket hit the wire. Physics took over. The wire didn’t break. The fence posts held. The cable was thinner than the gap between the tiger’s overlapping road wheels, but the angle was wrong.

Instead of slipping through, the wire caught on the bottom edge of the third road wheel. The forward momentum of the tank pulled the wire upward and inward. It wrapped around the wheel in a fraction of a second. One loop, two loops, three. The interleved wheels, the tiger’s brilliant, complex design, created a self-feeding trap.

As the wheel rotated, it drew more wire into the mechanism. The wire jammed between the second and third wheels. It happened faster than the driver could react. The wire wedged into the narrow gap. The rubber tire on the second wheel compressed against the wire. The third wheel pulled from the opposite direction.

The wire bit into the rubber. It found purchase. The tension increased exponentially. 200 lb of tensile strength multiplied by the mechanical advantage of the rotating wheels. The wire acted like a ratchet. Each rotation drew it tighter. The wheels locked together. The entire left side track assembly seized. The right track kept moving. The tiger pivoted violently to the left.

The driver felt the loss of control through the steering levers. He reacted instinctively. He gunned the engine. Wrong decision. The Maybach roared. 700 horsepower tried to drag the locked track forward. The right track dug into the road surface, throwing up dirt. The Tiger slew sideways. The locked left track acted like a pivot point. The tank rotated 15° in 2 seconds.

Something in the lof snapped. Not the wire. The wire held. It was a suspension arm that failed first. The torsion bar connecting the third road wheel to the hull fractured under the uneven load, then a mounting bracket. The Tiger lurched and stopped. The engine screamed. Black smoke poured from the exhaust as the governor tried to compensate for the sudden impossible load.

The driver killed the engine before it damaged itself further. Total elapsed time, 2.8 seconds. The Tiger sat motionless in the sunken road, caned at a 15° angle to the left, blocking the advance of the three tanks behind it. The commander stood in his hatch. He looked back. He looked forward. He screamed into his radio. Mallister didn’t speak German, but he understood panic when he heard it.

The tone, the urgency. The commander was reporting that his tank was immobilized. Cause unknown. Track damaged, blocking the road. He needed engineers. He needed recovery equipment. He needed the formation to halt. The Germans were trapped.

The road was too narrow for the tanks behind him to reverse and turn around, and they couldn’t bypass the lead tank. The hedge on either side were 4ft earth berms. The ground beyond was soft. A 56-tonon Tiger attempting to climb the burm would either bog down or throw a track. Either outcome would immobilize a second tank. They couldn’t abandon the vehicle. Doctrine prohibited leaving operational armor to the enemy.

They were trapped. Four Tigers in a linear formation on a single road with American infantry dug in on both flanks. It was the nightmare scenario. German armor doctrine was designed to prevent tanks without infantry support. Enclosed terrain, unable to maneuver, sitting targets.

The commander of the second Tiger tried to push the lead tank clear. He closed to within 5 m, lowered his blade, and revved his engine. The plan was to shove the disabled Tiger forward enough to create a gap. Maybe push it off the road entirely. The second Tiger’s engine roared. Its tracks spun, tore up the road surface through debris.

The disabled tank didn’t budge. Its locked left track acted like an anchor. The weight of the hull pressed down through the seized mechanism. 56 tons distributed across eight road wheels. The friction was enormous. After 30 seconds, the tracks on the second Tiger began to slip. Rubber tire rings smoked.

The commander gave up before he damaged his own vehicle. The Germans were now stationary targets. In a known location, Mallister’s lieutenant was already on the radio. Fire mission called in at 0626. Coordinates transmitted. Adjust fire. Three batteries of 105 mm howitzers acknowledged. Tubes elevated. Propellant charges loaded. High explosive shells.

Variable time fuses set for air burst. The trap was set. The bait was taken. And now the real hunters were on their way. The target was not the Tigers themselves. American artillery couldn’t penetrate a Tiger’s top armor from that distance. The target was the infantry supporting the tanks.

The first shells set for air burst impacted at 0630. They didn’t explode on the ground. They exploded 20 ft above the hedge, spraying thousands of red hot steel fragments downward in a cone of death. White phosphorus ignited the dry vegetation, creating a suffocating, burning smoke.

For the panzer grenaders hiding in the hedges, it was a slaughter. There was no cover from an attack that came from above. They broke. They scattered. Some tried to stay with the tanks, taking cover behind the massive hulls, only to be torn apart by the next salvo. Others fled back down the road, abandoning the armor.

Within 2 minutes, the Tigers were alone. Without infantry, they were blind and vulnerable. Their powerful 80 dimatum guns were useless against a target they couldn’t see. The crew served machine guns couldn’t depress low enough to engage targets at the base of the hulls. A single determined infantryman with a satchel charge could now approach from dead ground and destroy a multi-million reichmark machine. The Tigers were worth more than the men supporting them.

That was the cold mathematics of German armor doctrine in 1944. Trained tankers were irreplaceable. Each Tiger represented a strategic asset. Losing a tank was a strategic blow. Losing infantry was a tactical inconvenience. But now the irreplaceable asset was stuck. And the American forces were not going to let this opportunity pass.

22 Sherman platoon arrived at Oro645 four M4 A1 tanks. But these were not the old Shermans with the 75mm pop guns that bounced off Tiger armor. These were new. They carried the 76 mm high velocity gun. Longer barrels, higher muzzle velocity, a weapon capable of penetrating 4 in of armor at 500 m. The Sherman commanders knew the Tiger’s location.

They knew they were immobilized, and they knew the German infantry had scattered. They didn’t engage the lead tiger. They didn’t drive into the same trap. They bypassed it. They maneuvered through gaps in the bokeage that the Tigers couldn’t navigate. Lighter tanks, simpler suspension, narrower tracks. They used the terrain, the very terrain that had been a green hell for their own infantry.

As a weapon against the Tigers overengineered perfection, they reached firing positions 300 meters behind the German formation. The Tigers were facing the wrong direction. Their turrets could traverse, but slowly, 62 seconds for a full 360° rotation. The Shermans had 30 seconds to fire before the Tigers could bring their main guns to bear.

At 0650, all four Shermans fired simultaneously. They didn’t target the frontal armor. They didn’t even target the side plates. They targeted the rearmost Tiger’s engine deck. The thinnest armor on the entire vehicle, 25 mm, angled, but not steeply enough. Three 76 mm armor-piercing shells penetrated. They punched through the thin steel deck and into the engine compartment.

One struck the fuel tanks. The Tiger erupted. Not a Hollywood explosion. A rapid, violent expansion of burning fuel and smoke. Flames poured from the engine grills. Thick black smoke from burning rubber and oil. The crew had 15 seconds to evacuate before the ammunition cooked off. Five men emerged, three from the turret hatches, two from the hull.

Two of them were on fire. They rolled in the dirt, screaming. The remaining Tigers surrendered at 700. Crews emerged, hands raised high, white undershirts tied to their radio antennas. The mathematics had shifted. Three Tigers trapped on a narrow road. American armor behind them. American artillery zeroed in on their position. American infantry closing in from the flanks. No infantry support.

No way to maneuver. No way to win. Surrender was the only rational choice. live to be exchanged or repatriated. Better than burning to death inside a 56-tonon steel coffin. The disabled lead tiger, Malister’s tiger, was towed to a field workshop for analysis. American engineers swarmed over it. They photographed every detail. They measured the armor thickness.

They examined the running gear and they found the wire. It was still wrapped around the road wheels. They needed cutting torches to remove it. The wire had bitten so deeply into the rubber tires that it had scored the steel underneath. The autopsy was clinical. The suspension arm was fractured. The torsion bar was cracked. The mounting bracket was bent.

Total repair time 12 hours. The parts were available from captured stocks. The Tiger was operational again by evening, but it never returned to combat. Fuel shortages kept it immobilized for the rest of the campaign. By August, it sat in a depot south of St. Low, awaiting fuel that never arrived. In September, the crew was reassigned.

In October, advancing American units captured the depot. The Tiger was loaded onto a flatbed and shipped to the Aberdine proving ground in Maryland for evaluation. Mallister’s commanding officer submitted him for a bronze star. The citation was brief. Bureaucratic language for innovative action resulting in the neutralization of enemy armor.

The paperwork traveled up the chain of command, battalion, regiment, division. The medal was approved in August. It was presented in September at a formation in a muddy field outside Aken. And then James Mallister went back to work. After the war, he returned to Pittsburgh. He used the GI Bill to finish an engineering degree.

He worked as an electrician for 31 years. A union man, steady employment. He married in 1947. He had three children. He retired in 1976. He died in 1989 from complications of lung cancer. His obituary in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette mentioned his military service in one sentence. Bronze Star recipient, combat engineer Normandy to the Elba.

The orbituary said nothing about the wire, nothing about the tiger. His family knew he’d been in the war. They didn’t know the details, but word spread among combat engineers. The story became a legend. After action reports circulated, the wire trick appeared in intelligence summaries. Field manuals were updated. By July 1944, engineer companies across the European theater were carrying extra coils of wire.

Not for communications, for traps. Some tried to replicate Malister’s success. The results were mixed. The wire worked against tigers and panthers when conditions aligned. Narrow roads, firm anchors, surprise, the right angle of approach, but it failed against lighter tanks with simpler running gear. It failed in mud where the wire sank before the tank reached it. It failed when tank crews learned to watch for it.

German field manuals were updated in August. Warnings about cable traps appeared in technical bulletins distributed to panzer units. Crews were ordered to have one man walk ahead of the formation in close terrain to cut any suspicious wires to machine gun the base of hedros before advancing. The counter measures were effective. By September, the wire trick rarely worked.

The tactical window was brief, June to August 1944, 3 months, but its impact was documented. At least 11 Tiger and Panther tanks were immobilized by wire traps during that period. not destroyed, not captured, just stopped, forced to halt in exposed positions where they could be flanked or bypassed or destroyed by indirect fire.

In the mathematics of armored warfare, a stopped tank was often as valuable as a dead one. It blocked roads. It consumed resources. It required recovery. It tied up engineers and mechanics. And the Tiger itself represented Germany’s strategic dilemma. It was overengineered, expensive, maintenance intensive.

It was tactically dominant but strategically irrelevant. Germany produced 188 at 84 Tiger when tanks between 1942 and 1944. In that same period, the Soviet Union produced 57,000 to T34s. The United States built 49,000 Sherman’s quality could not compensate for quantity at that scale. Every Tiger destroyed was irreplaceable. Every Tiger stopped was a resource wasted.

Every hour spent repairing one tiger was an hour not spent repairing three Panthers or six Panzer IVs. The interleved wheel design, the Lurk that made the Tiger so capable was its downfall. It was optimal engineering for ideal conditions. It was catastrophic in the field. The overlapping wheels distributed weight beautifully.

When clean and maintained, they jammed catastrophically when fouled. The design required peace to function properly. It needed smooth terrain, dry conditions, and regular maintenance. War provided none of these. The Bokeh was mud and wire and debris. The Eastern Front was frozen mud in winter, liquid mud in spring. North Africa was sand and grit.

Every single environment exposed the tiger’s vulnerability. The wire trap exposed a deeper truth about complex systems. They fail in simple ways. The more sophisticated the design, the more fragile it becomes. The Tiger’s interleved wheels were optimal for weight distribution. They created vulnerabilities that simpler designs avoided.

The Sherman’s vertical vollet suspension was crude by comparison. Five road wheels per side, no overlap, no interle, just coil springs and shock absorbers. It provided a rougher ride. It created higher ground pressure, but it was also modular, repairable, resistant to fouling. A Sherman crew could replace a road wheel in 20 minutes.

With basic tools, a Tiger crew needed half a day and specialized equipment to change an inner wheel. This principle extended beyond armor. Luftvaf mi262 jet fighter was 100 mph, faster than anything the allies fielded, but its engines lasted 12 hours before needing replacement. and it required smooth concrete runways that Allied bombers destroyed nightly.

Germany’s V2 rocket was a technical marvel. It also cost as much as a 4engine bomber and delivered a one-tonon warhead with poor accuracy. Germany’s wonder weapons were marvels of engineering and studies in impracticality. They won battles. They lost wars. They demonstrated technical superiority and strategic bankruptcy.

They proved that sophistication without sustainability is a path to defeat. The Allies won with simpler weapons produced in overwhelming numbers. The Sherman was inferior to the Tiger in direct combat. But America built 50 Shermans for every Tiger Germany produced. Mallister understood none of this.

He wasn’t a strategic analyst. He was an electrician who knew how machines failed. He saw a gap in the wheels and thought about jamming it. There was no grand strategy, no sophisticated analysis, no deep understanding of German engineering philosophy, just a man with 300 ft of wire and 90 seconds to act.

Just the desperate calculation that anything was worth trying. If the alternative was certain death, that was enough. The war didn’t turn on wire traps. It turned on logistics, industrial capacity, and mathematics. But individual actions mattered in local contexts. A disabled tiger saved 32 lives in one hedger. And the wire trap endures.

It appears in training manuals at Fort Moore, case studies at the Army Engineer School, academic papers on improvised anti-tank measures. It represents something essential about warfare that transcends technology. Complexity creates fragility. Ingenuity finds weakness. Desperation breeds innovation. Mallister never claimed to be innovative.

In his only recorded interview given in 1987 to a local newspaper researching veteran stories, he said, “I just didn’t want to die that morning. The wire was in my hand. The posts were right there. It seemed worth trying. I didn’t think it would work, but doing nothing definitely wasn’t going to work. Worth trying. Two words that summarize battlefield innovation across centuries. Most attempts fail.

A few succeed. The successful ones get remembered, analyzed, mythologized. The failures vanish into the noise of combat. The difference is often luck. If Mallister’s wire had been 6 in higher, the Tiger would have driven under it. If the posts had been rotten, they would have snapped.

If the commander had been more cautious, he would have sent infantry ahead, but the variables aligned. The wire held, the trap jammed, the formation halted, the Shermans flanked, the Germans surrendered, Malister survived. The Tiger. I was retired from production in August 1944. Germany shifted resources to the Tiger 2, which had even thicker armor and even more complex mechanics.

It also had overlapping wheels. The vulnerabilities remained. Modern armor designers remember this. Contemporary main battle tanks use fewer, larger road wheels. Six per side on the M1 Abrams, seven on the Leopard 2. Simplified suspension systems that prioritize maintainability over optimal ride quality.

The lessons learned from the Tigers. Failures were incorporated into every tank design. Since elegance is valuable, reliability is essential. Complexity without robustness is a liability. June 1944 taught that lesson in blood and steel. Mallister taught it with wire and 90 seconds of courage. Mallister’s wire is preserved today.

The Infantry Museum at Fort Moore, Georgia houses it in a climate controlled case. It’s displayed with a typed card explaining its use. Most visitors walk past it without stopping. The wire looks unremarkable. frayed steel cable, rust spots, faded green fabric insulation. Nothing dramatic, nothing that suggests its significance. But it stopped a machine designed to be unstoppable.

It proved that 56 tons of armor, 4 in of hardened steel, and 700 horsepower could be defeated by 8 ounces of wire applied at the right point with the right timing. It demonstrated that every system, no matter how sophisticated, has vulnerabilities. The lesson isn’t about wire. It’s about seeing systems as they are, not as they’re intended to be.

The Tiger was intended to dominate. But it was also a collection of components under stress. Wheels and tracks and pins and brackets. Each one a potential failure point. Mallister didn’t attack the Tiger’s strengths. He targeted a seam in its complexity. He found the point where sophistication became vulnerability.

News

My husband texted me out of nowhere: “I’m done with us. I’m taking off to Miami with my 20-year-old girlfriend, and I took every last dollar from our joint account, lol.” I only replied: “Good luck.” By the time the truth hit him, everything was beyond repair…

When the message arrived, I was standing in the middle of the checkout line at a Target in Cleveland, holding…

I inherited $900,000 from my grandparents, while the rest of my family got nothing. Enraged, they banded together and demanded I vacate the house by Friday. Mom sneered, “Some people don’t deserve nice things.” I smiled and said, “You think I’d let that happen after everything I know about this family?” Two days later, they arrived with movers and smug grins—only to freeze when they saw who was waiting on the porch.

My name is Clare, and at 28, I had become intimately familiar with the corrosive nature of grief and greed….

At a family barbecue, my little girl fell from the playground and was rushed to the hospital in a coma. I was holding her hand when my son came up and whispered: “Mom… I know what really happened.” My heart stopped. “What did you see?” I asked him. He opened his mouth to speak, but before a single word came out, the hospital door burst open…

The smell of roasted corn and smoked meat still lingered on my hands when everything changed. We’d gathered at my…

“He crawled out of a forgotten basement with a broken leg, dragging his dying little sister toward the only ray of light left. His escape wasn’t just survival: it was a silent scream the world needed to hear.”

The darkness in the Brennans’ basement wasn’t just the absence of light: Oliver Brennan had begun to believe she was…

When I went to my ex-wife’s house to pick up our daughter, I noticed red marks on her back. Her new boyfriend just laughed and said, “They’re just little marks.” I smiled and replied, “Thank you… that helps me more than you think.” The girl didn’t want to take off her hoodie, but my ex ended up lifting the garment. Then I saw it: a massive mandala tattooed on her back. “She said she wanted to look strong, like in the movies,” my ex commented as if it were no big deal. But what happened next… was something I never imagined.

When I arrived at my ex-wife’s house to pick up our daughter, the last thing I expected was to feel…

During a family dinner, I stood up smiling and announced I was pregnant. The entire table fell completely silent; then, my mother-in-law suddenly burst out laughing and yelled: ‘She’s faking her pregnancy just to get money from us!’ Before anyone could react, she grabbed my hand and shoved me from the hotel rooftop ‘to prove’ I was faking it. Shattered and barely conscious, I woke up in the hospital with my husband beside me, pale as a ghost and trembling. But the moment the doctor walked in and opened his mouth, the words he said froze the entire room in absolute disbelief and horror.

“The moment I stood up during the family dinner, gently placing a hand on my stomach, I felt both nervous…

End of content

No more pages to load