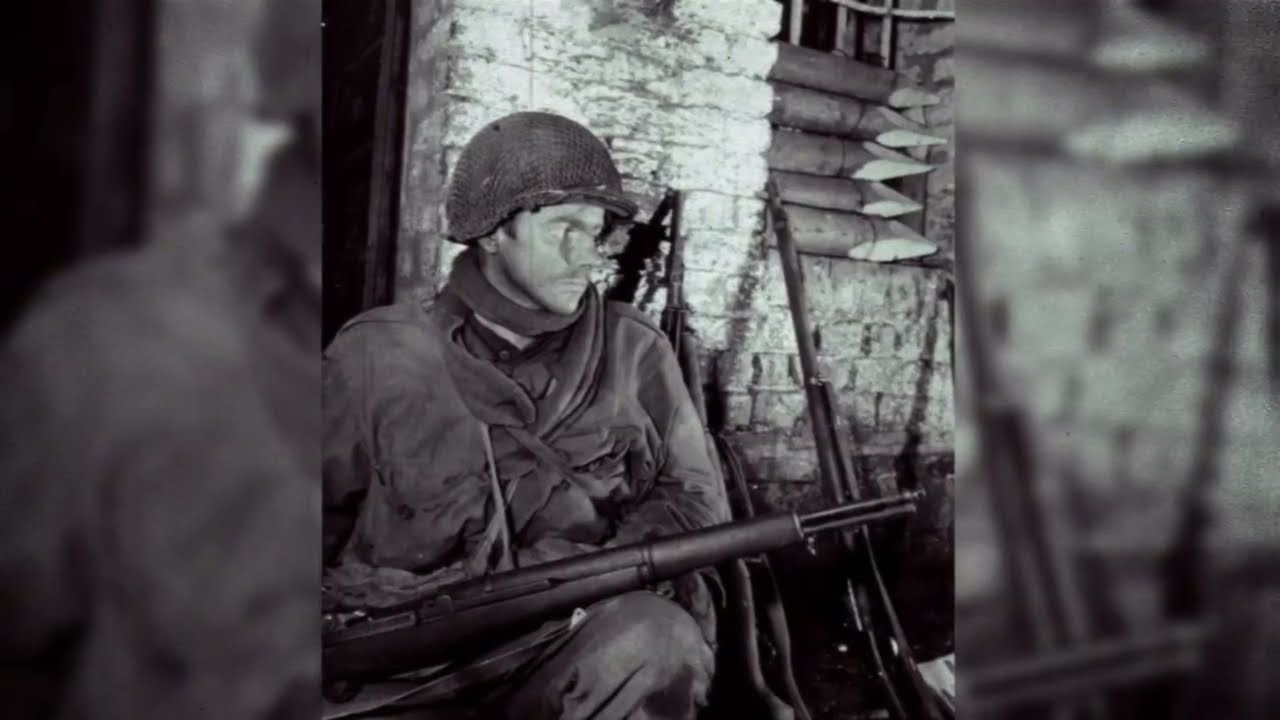

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese bunker west of Point Cruz, watching a banyan tree 240 yard away through a scope his fellow officers had laughed at for 6 weeks. 27 years old, Illinois state champion, zero confirmed kills.

The Japanese had 11 snipers operating in the Point Cruise Groves, and in the past 72 hours, they had killed 14 men from the 132nd Infantry Regiment. George’s commanding officer had called his rifle a toy. The other platoon leaders called it his male order sweetheart. When he had unpacked the Winchester Model 70 with its Lyman Alaskan scope and Griffin and how mount at Camp Forest in Tennessee, the armorer wanted to know if this was meant for deer or Germans.

George explained it was for the Japanese. They shipped out before the rifle arrived. George spent the voyage to Guadal Canal watching other men clean their Garands while his own weapon sat in a warehouse in Illinois. He requested it be forwarded through military mail.

6 weeks later in late December of 1942, a supply sergeant handed him a wooden crate marked fragile. Inside was the rifle he had saved 2 years of National Guard pay to buy. The rifle weighed 9 lb. The scope added another 12 o. The grand issued to every other man in his battalion weighed 9 12 lb with no magnification.

George’s rifle was boltaction, five rounds. The Garand was semi-automatic, eight rounds. Captain Morris ordered him to leave the sporting rifle in his tent and carry a real weapon. George carried it anyway. The 132nd Infantry had relieved the Marines on Guadal Canal in late December of 1942. The Marines had been fighting since August. They had taken Henderson Field.

They had held it, but they had not taken Mount Austin, and they had not cleared the Japanese from the coastal groves west of the Matanakau River. Mount Austin stood 1514 ft tall. The Japanese called it the GEU, 500 men, 47 bunkers. George’s battalion attacked on December 17th. They fought for 16 days. They lost 34 men killed and 279 wounded before they finally took the Western Slope on January 2nd.

By then, George had fired his Winchester exactly zero times in combat. The jungle around Point Cruz was different. No bunkers, no fixed positions, just Japanese soldiers who had retreated west from Henderson Field and dug into the massive trees. Some of those soldiers were snipers. They had scoped Arisaka Type 98s. They knew the jungle. They knew how to wait.

On January 19th, a sniper killed Corpal Davis while he was filling cantens at a creek. On January 20th, another sniper killed two men from L Company during a patrol. On January 21st, three more men died. One of them was shot through the neck from a tree the patrol had walked past twice. The battalion commander summoned George that night. The Japanese snipers were killing his men faster than malaria. He needed someone who could shoot.

He wanted to know if that mail order rifle could actually hit anything. George explained his credentials. Illinois State Championship at 1,00 yards in 1939. 23 years old at the time, youngest winner in the state’s history, 6-in groups at 600 yards with iron sights with the Limeman Alaskan five rounds inside 4 in at 300 yards.

The commander gave him until morning to prove it. If you want to see how George’s civilian rifle performed against Japanese snipers trained for jungle warfare, please hit that like button. It helps us share more forgotten stories like this. And please subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to George. George spent the night checking his rifle.

The Winchester had been packed in cosmoline for the ocean voyage. He cleaned it again. He checked the scope mounts. He loaded five rounds of 306 hunting ammunition he had packed in Tennessee. Military ball ammo. The same cartridge the Garand fired. At dawn on January 22nd, George moved into position in the ruins of a Japanese bunker his battalion had captured 3 days earlier.

The bunker overlooked the coconut groves west of Point Cruz. Intelligence said the Japanese snipers operated from the large trees in that area, banyan trees. Some of them reached 90 ft tall with trunks 8 ft thick. A sniper could climb one of those trees before dawn and sit there all day without being seen. George had brought no spotter, no radioman, just his rifle and a canteen and 60 rounds of ammunition in stripper clips. He settled into the bunker and began to watch the trees through his scope.

The Lyman Alaskan had two and a half power magnification. Not much, but enough to see movement in the branches that the naked eye would miss. The jungle was never silent. Birds, insects, the distant sound of artillery. George had learned to filter out the noise and focus on movement. He glassed the tree slowly, left to right, top to bottom. At 917, he saw it. A branch moved.

No wind, just a small shift. 87 ft up in a banyan tree 240 yard away. George watched. The branch moved again. Then he saw the shape. A man, dark clothing, positioned in a fork where three branches met. The Japanese sniper was facing east, watching the trail where George’s battalion had been moving supplies.

George adjusted his scope, two clicks right for wind. He controlled his breathing. The Winchester’s trigger was glass smooth, 32 lb. He had spent hours adjusting it at Camp Perry before the war. Now he would find out if a civilian target rifle could kill a man trained to kill him first. George squeezed the trigger. The Winchester kicked into his shoulder.

The sound cracked through the jungle. 240 yd away. The Japanese sniper jerked and fell. He dropped through the branches. His body tumbled 90 ft and hit the ground near the base of the banyan tree. George worked the bolt. The empty cartridge ejected. He chambered another round. He kept his scope on the tree, waited for movement. Nothing. The sniper’s partner would be close.

Japanese snipers worked in pairs. One shooter, one spotter. If George had just killed the shooter, the spotter was somewhere in that tree or in the trees nearby. George scanned the surrounding banyions. The scope’s 2 and 1 half power magnification forced him to search slowly.

Each tree could hide multiple men. The jungle canopy created shadows that made shapes impossible to distinguish without careful observation. At 9:43, he found the second sniper. Different tree, 60 yards north of the first. This one was lower, maybe 50 ft up. The Japanese soldier was moving down the trunk, retreating. He had heard the shot and knew his position was compromised.

George aimed, led the movement, fired. The second sniper fell backwards off the tree. His rifle clattered through the branches ahead of him. Both hit the jungle floor within seconds of each other. Two shots, two kills. George reloaded his Winchester from a stripper clip. His hands were steady. His breathing was controlled. This was no different than shooting at Camp Perry, except the targets shot back.

At 11:21, a Japanese bullet struck the sandbag 6 in from George’s head. The impact sprayed dirt into his face. He rolled left and pressed himself against the bunker wall. The shot had come from the southwest. Different direction than the first two snipers. George waited 3 minutes before moving. He inched back to his firing position and glassed the trees to the southwest.

The shooter would have moved after taking the shot. That was basic sniper doctrine. shoot and relocate. But in a jungle this dense, relocation options were limited. George found him at 11:38, third tree from the left in a cluster of five bany 73 ft up. The Japanese sniper had repositioned to a different branch, but remained in the same tree. A mistake.

George put the crosshairs on the dark shape and fired. The third sniper fell without making a sound. By noon, George had killed five Japanese snipers. Word spread through the battalion. Men who had mocked his mail order rifle now asked if they could watch him work. George refused. Spectators drew attention. Attention drew fire.

The Japanese snipers adapted after the fifth kill. They stopped moving during daylight. George spent the afternoon glassing trees and seeing nothing. At 1600 hours, he returned to battalion headquarters. Captain Morris was waiting. The mockery was gone from his voice. He wanted George back in position at dawn. January 23rd began with rain, heavy tropical rain that turned the jungle floor into mud and made the trees invisible beyond 100 yard.

George sat in the bunker and waited for the weather to clear. The rain stopped at 08:15. By 08:45, enough visibility had returned for work. George spotted the first sniper of the day at 0912. The Japanese soldier had climbed into position during the rain. Smart. The sound of rain masked movement. This sniper had chosen a tree 290 yd out, longer range than yesterday. Also smart. They were learning his capabilities.

George compensated for distance and fired. The sniper fell. The sixth kill brought a response George had not anticipated. At 0957, Japanese mortars began hitting the area around his bunker. They had triangulated his position based on muzzle flash or sound. The first rounds landed 40 yard short. The second salvo landed 20 yard short. The third salvo would hit the bunker.

George grabbed his rifle and ran. He sprinted north along the treeine and dove into a shell crater. As the third salvo hit, the bunker he had occupied moments before disappeared in explosions and flying debris. He relocated to a different position. A fallen tree 120 yard north of the destroyed bunker. The tree provided cover and a clear view of the groves. George settled in and resumed his watch.

The Japanese sent more snipers that afternoon. They knew George was hunting them. They were now hunting him back. The dynamic had changed. This was no longer target shooting. This was a duel. At 1423, George killed his seventh sniper. At 1541, he killed his eighth. This one had climbed high, 94 ft up a banyan tree.

Good concealment, but the height created a silhouette against the sky when the sun angle changed. At 1700 hours, Captain Morris sent a runner to bring George back. George had been in position for 9 hours. Morris wanted numbers. George reported eight confirmed kills over two days. 12 rounds fired, eight kills, four misses. Morris assigned George to continue sniper operations starting at dawn on January 24th.

That night, George cleaned his Winchester and considered the mathematics. 11 Japanese snipers operating in the Point Cruz groves. Eight now dead, three remaining. Those three would be the best. the ones who had survived the longest. And now they knew exactly what George looked like and exactly what rifle he carried. George loaded his Winchester with five fresh rounds and tried to sleep.

At 0300, he gave up and sat in his tent with the rifle across his lap. The rain started again at 04:15. By 0530, it was heavy enough that dawn operations would be delayed. George used the time to move to a new position. Not the bunker, not the fallen tree. somewhere the Japanese would not expect.

He chose a spot 70 yard south of his previous position, a cluster of large rocks the Marines had used as a machine gun nest back in December. The position offered good cover and overlapping fields of fire into the groves. He settled in and waited for the rain to stop. At 0743, the rain slowed to a drizzle. Visibility improved. George began glassing trees.

At 0817 on January 24th, he found sniper number 9. The Japanese soldier was positioned in a palm tree 190 yard out. Low, only 40 ft up. Unusual. Most snipers climbed high for better sightelines. This one had chosen concealment over elevation. The palm frrons created a natural hide that would be invisible from ground level. But George was not at ground level.

He was elevated on the rocks. The angle gave him a view down into the fronds. He could see the dark shape of the sniper’s shoulders and head. George aimed, controlled his breathing, began to squeeze the trigger. Then he stopped. Something was wrong. The position was too obvious, too easy. George had been hunting snipers for 3 days. He had killed eight men. The remaining three would not make elementary mistakes.

They would not position themselves where an elevated shooter could spot them unless it was bait. George lowered his rifle and scanned the surrounding trees. If the sniper in the palm was bait, the real shooter would be positioned to cover him, watching for anyone who took the shot, waiting for muzzle flash, ready to return fire.

George glassed the trees methodically, left to right, top to bottom. He checked every tree within 300 yards of the palm. It took 11 minutes. At 0828, he found the real threat. A banyan tree 80 yard northwest of the palm, 91 ft up. The Japanese sniper was positioned in a perfect hide. Branches and vines concealed him from three sides.

He had a clear line of sight to George’s previous position at the fallen tree. He was waiting for George to appear there or to take a shot at the bait in the palm tree. George had two problems. First, the real sniper was watching the wrong location. If George fired at him, the sound would reveal George’s actual position.

The sniper would relocate before George could work the bolt and chamber another round. Second, if George did nothing, the sniper would eventually realize George was not at the fallen tree and begin searching for him. George decided to use the bait against them. He aimed at the decoy sniper in the palm tree, adjusted for wind, fired. The decoy sniper jerked, and fell from the palm.

George immediately swung his rifle toward the banyan tree 91 ft up. The real sniper would react to the shot. He would turn toward the sound. That turn would create movement. George saw it. A slight shift. The sniper was repositioning to face George’s location.

George put the crosshairs on the dark shape and fired before the sniper could fully turn. The real sniper fell. His rifle tumbled after him. Two shots, two kills. But George had revealed his position to anyone else watching. He grabbed his rifle and ammunition and ran. He moved east along the rock line and dropped into a drainage ditch 40 yard away. He pressed himself into the mud and waited.

At 0834, Japanese machine gun fire raked the rocks where he had been positioned 6 seconds earlier. The bullets kicked up dust and stone fragments. The fire lasted 17 seconds. When it stopped, George counted to 60 before moving. He relocated again, this time to a position 100 yardds east, a shell crater partially filled with rainwater. George settled into the crater with water up to his chest.

He rested the Winchester on the crater rim and resumed glassing trees. 10 confirmed kills, one remaining. The 11th sniper would be the best, the smartest, the most experienced. He had watched 10 of his comrades die over 3 days. He knew George’s tactics. He knew George’s rifle. He knew George’s approximate location. And somewhere in those trees, he was watching, waiting, planning.

George scanned the jungle through his scope. The Lyman Alaskan magnification made distant shapes visible, but not identifiable. Every dark spot could be a branch or a man. George had to study each one carefully. At 0947, he realized his mistake. The 11th sniper was not in the trees. He was on the ground, and he was moving toward George’s position.

George saw the movement at the edge of his peripheral vision, 60 yard south, low to the ground. A shape moving through the undergrowth parallel to the tree line. The Japanese sniper was using the jungle floor vegetation for cover. Ferns, vines, fallen branches.

He was crawling toward George’s last known position at the rocks. George remained motionless in the water-filled crater. The Winchester was already shouldered. His breathing was controlled, but the angle was wrong. The crater rim blocked his view of the approaching sniper. George would have to rise up to get a clear shot. Rising up would expose him.

The Japanese sniper stopped moving at 0952. He had reached a position 40 yard from the rocks. George watched through his scope. The sniper was studying the rocks, searching for movement for any sign of his target. George waited. Patience was the primary skill of sniper work.

The ability to remain still, to let time pass, to wait for the right moment rather than force a bad shot. At 0958, the Japanese sniper began moving again. He crawled forward 35 yd from the rocks. 30 yards, 25 yards. He was approaching from the south side, the side George had used when he evacuated under machine gun fire. George understood the tactic.

The Japanese sniper had watched the machine gun attack. He knew George had moved east from the rocks. He was now working his way along the most likely escape route, hunting George the way George had been hunting him. At 10:03, the Japanese sniper reached the rocks.

He moved into the machine gun nest and took up a position facing east toward the drainage ditch toward the area where George should have relocated. The sniper was now 38 yd from George’s actual position in the water-filled crater, but he was facing the wrong direction. His back was exposed. George had a clear shot. Center mass 38 yd. An easy shot even without a scope. But George hesitated. This sniper had survived 10 days of American operations in the Point Cruz Groves.

He had outlived 10 other snipers. Men who had been killed because they made mistakes. This man would not make mistakes. The position in the rocks was too exposed, too vulnerable. No experienced sniper would remain there for more than a few seconds. This had to be another decoy, another bake position. George kept his scope on the sniper in the rocks, but expanded his awareness to the surrounding area.

If this was bait, the real threat would be positioned to cover it somewhere with line of sight to anyone who took the shot. At 10:06, George found it. A second Japanese soldier 70 yard northwest of the rocks behind a fallen tree trunk. This soldier was not moving, not repositioning, just watching, waiting.

His rifle was aimed toward the drainage ditch where George should have been hiding. Two men, not one. The 11th sniper had brought support. Or perhaps these were the final two snipers, numbers 10 and 11, working together. George made his decision. He could not shoot both men before they reacted. The bolt-action Winchester required him to work the action between shots.

That gave them time to locate him and return fire. He needed a different approach. George slowly lowered himself deeper into the water. He submerged until only his eyes and the top of his head remained above the surface. He kept the Winchester pointed skyward to keep water out of the barrel. Then he waited.

At 10:13, the Japanese soldier in the rocks stood up. He had spent 10 minutes watching the drainage ditch and seen nothing. He believed George had moved farther east. He turned and signaled to his partner behind the fallen tree. Both men began moving east, parallel to each other, 70 yards apart.

They were executing a sweep, planning to flush George out or find his position. George remained in the water, motionless. The two Japanese soldiers moved past his crater. They were now between George and the treeine. Their backs were exposed. George rose from the water. Slowly, silently, he brought the Winchester to his shoulder. Water dripped from the barrel, from his uniform, from his face.

He aimed at the closer soldier, the one who had been in the rocks, now 42 yards away. George fired. The soldier dropped. George worked the bolt, chambered another round, swung the rifle toward the second soldier behind the fallen tree. The man was turning, raising his rifle. George fired first.

The second soldier fell. 11 shots fired over three days. 11 Japanese snipers dead. George had cleared the point crews groves of the threat that had killed 14 Americans in 72 hours. But as George climbed out of the crater and retrieved his spent cartridges, he heard a sound that made him freeze. Voices. Japanese voices coming from the treeine.

Multiple men moving toward the fallen soldiers. George had killed the snipers, but the snipers had not been working alone. George dropped back into the crater. The water was cold, muddy. He submerged until only his eyes remained above the surface. The Winchester he held vertically to keep the barrel clear.

The Japanese voices grew louder. At least six men, maybe more. They were moving toward the two dead snipers. George heard branches breaking, equipment rattling. These were not snipers. Infantry. A patrol or recovery team sent to collect the bodies. George counted seconds.

The voices stopped at the location of the first body 42 yards from his crater. Close enough that he could hear them clearly, even without understanding the words. Then the voices moved to the second body. More conversation, urgent tones. At 10:28, the voices began moving again, not back toward the treeine, toward George’s crater. They had found his tracks. Bootprints in the mud leading from the rocks to the crater.

George had been careful about noise and movement. He had not been careful about tracks. George had five rounds in the Winchester, six Japanese soldiers at minimum. Poor odds for a boltaction rifle. He considered his options. Stay hidden and hope they passed by or fight. The voices grew closer. 30 yards, 25 yards, 20 yards. At 10:31, a Japanese soldier appeared at the crater rim.

He was looking down directly at George. Their eyes met. George fired from the water. The soldier fell backward. George worked the bolt while still submerged, chambered another round, rose up. Two more soldiers were at the crater rim. George fired, worked the bolt, fired again. Both soldiers dropped. Three rounds left. George could hear shouting.

More soldiers moving toward him. He climbed out of the crater on the north side, away from the approaching voices. He ran 20 yards and dropped behind a fallen tree. Japanese rifle fire cracked through the jungle. Bullets struck the ground around the crater around the fallen tree.

The soldiers were firing at movement, at sound, not at confirmed targets. George stayed low. He glassed the area through a scope. Saw movement. Two soldiers advancing toward the crater. 50 yards out. George aimed at the lead soldier. Fired. The soldier dropped. The second soldier dove for cover. Two rounds left. George heard more voices behind him.

The Japanese were flanking. One group approaching from the south, another from the east. George was about to be surrounded. He made his decision. He could not win a firefight with a bolt-action rifle against multiple soldiers with semi-automatic weapons. He needed to break contact, move back toward American lines. George grabbed his rifle and ran north. He sprinted through the jungle undergrowth. Vines caught his boots.

Branches whipped his face. Japanese rifle fire followed him. Bullets snapped past, struck trees, kicked up dirt. George ran for 90 seconds before diving into another shell crater. This one was dry. He pressed himself against the crater wall and listened. The Japanese voices were distant now. They had not pursued. They were regrouping around their dead. George checked his rifle.

Mud on the stock, water still dripping from the barrel. He had two rounds left and no stripper clips. The clips were in his pack. The pack was somewhere near the water-filled crater. At 10:47, George began moving again, not running, walking, staying low, using the terrain for cover. He moved northeast toward the American lines. The jungle was quiet.

No voices, no movement, just the sound of his own breathing and the distant rumble of artillery. At 11:13, George reached the American perimeter. A Marine sentry challenged him. George identified himself. The sentry led him through. George walked to battalion headquarters and reported to Captain Morris. Morris wanted a full debrief. George provided it.

11 Japanese snipers killed over 4 days. 12 rounds fired against the snipers. 11 hits. Then a firefight with infantry. Three more kills. Five total rounds in that engagement. Morris asked about ammunition status. George was down to two rounds. Morris asked about the rifle. George said it was functional but needed cleaning. Mud in the action. Water in the barrel.

Morris told George to clean his rifle and rest. No operations tomorrow. The battalion was moving east. The point cruise groves were no longer a priority. The Japanese were evacuating Guad Canal. Intelligence suggested they would complete the withdrawal within two weeks. George returned to his tent. He field stripped the Winchester and spent two hours cleaning every component. Cosmoline and gun oil.

Patches run through the barrel until they came out clean. He checked the scope mounts, adjusted the eye relief, loaded five fresh rounds. At 1400 hours, word came down from division headquarters. The battalion commander wanted to see George. George walked to headquarters wondering if Morris had filed a negative report.

Unauthorized engagement, excessive ammunition expenditure, operating alone without support. Instead, he found Morris and two other officers waiting. One of them was Colonel Ferry, the regimental commander. Ferry had one question. Could George train other men to do what he had done? George said he could try, but it would require time and rifles with optics and men who could already shoot.

Ferry said division had 14 Springfield rifles with unertle scopes, sniper rifles left behind by the Marines and Ferry had 40 men in the regiment who had qualified as expert marksmen before deployment. Ferry wanted George to create a sniper section, train the men, develop tactics, clear any remaining Japanese snipers from American operational areas. George accepted, but he had one condition.

He wanted to keep his Winchester. Ferry approved the request. George kept his Winchester Model 70. The 14 Springfield rifles with Unertle scopes went to the men George would train. Training began on January 27th. George had 40 men assembled at a makeshift range two miles east of Henderson Field. The men were expert marksmen on paper.

They had qualified with iron sights at ranges up to 500 yardds, but none of them had combat experience as snipers. None of them had killed a man from concealment. George started with the fundamentals: breathing control, trigger squeeze, reading wind. The Springfield rifles weighed 11 lb with the Unertle scopes.

Heavier than the Grand, heavier than George’s Winchester. The weight made the rifles stable but tiring to hold for extended periods. George taught them to use any available support, rocks, logs, sandbags. The jungle rarely offered perfect shooting positions. Snipers had to adapt to terrain and create stable platforms from whatever materials were available. Range training lasted 3 days.

George had the men shoot at stationary targets from 100 to 400 yd, then moving targets, then targets partially concealed by vegetation. By January 30th, 32 of the 40 men could consistently hit man-sized targets at 300 yd under field conditions. George divided them into 16 twoman teams, shooter and spotter.

The spotter carried binoculars and a grand. His job was to locate targets and provide security while the shooter engaged. After each kill, the roles could switch. This kept both men proficient and prevented the single point of failure that came from relying on one shooter. On February 1st, George took four teams into the field.

Their mission was to clear Japanese positions west of the Matanakau River. Intelligence indicated small groups of Japanese soldiers were still operating in that area. Not snipers, just infantry. stragglers who had not yet evacuated. The four teams moved into position at dawn. George paired with a spotter named Corporal Hayes.

They set up on high ground overlooking a trail the Japanese had been using for resupply. At 0720, a Japanese soldier appeared on the trail. Hayes confirmed the target through binoculars. George fired. The soldier dropped. George worked the bolt and scanned for additional targets. None appeared. Over the next six hours, George’s team engaged seven more Japanese soldiers on that trail.

Seven shots, six kills, one miss due to wind. The other three teams reported similar results. 23 Japanese soldiers killed that day. Zero American casualties. The sniper section continued operations through early February. By February 9th, the section had killed 74 Japanese soldiers. The number was conservative, only counted confirmed kills where the body could be observed.

The Japanese evacuation accelerated during this period. Destroyers arrived at night to pick up troops from Cape Espirans on the western tip of Guad Canal. American forces pushed west to interdict the evacuation, but the Japanese fought effective rear guard actions. George’s sniper section was tasked with eliminating Japanese soldiers covering the retreat routes.

On February 7th, George was operating near the Tanam Boa River when a Japanese rifleman shot him. The bullet struck George in the left shoulder. The impact spun him around and knocked him down. Hayes dragged George to cover and called for a corman. The wound was serious, but not fatal. The bullet had passed through muscle without hitting bone or major blood vessels.

George was evacuated to a field hospital near Henderson Field. Doctors cleaned the wound and sutured it closed. They told George he would recover, but needed rest. No combat operations for at least 3 weeks. George spent two weeks at the field hospital. During that time, the Japanese completed their evacuation of Guad Canal.

On February 9th, American forces reached Cape Espirans and found it empty. The campaign was over. George’s sniper section had operated for 12 days. 74 confirmed kills, zero friendly casualties during sniper operations. The section was officially recognized by division headquarters. Colonel Ferry recommended George for a bronze star. But George’s war was not finished.

While he recovered at the field hospital, orders came down from Pacific Command. The army needed experienced combat officers for a new mission, something in Burma, something classified. George volunteered. By March, George was on a transport ship heading west across the Pacific. His Winchester Model 70 was packed in a waterproof case in the cargo hold.

The Lyman Alaskan scope was wrapped in oil cloth. George did not know the details of the Burma mission. He only knew it involved jungle warfare, long range patrols, operations behind Japanese lines. The kind of mission where a man with a rifle that could hit targets at 600 yardds might prove useful.

The transport reached India on April 3rd. George and 200 other officers were briefed on their assignment. They would join a new unit, 3,000 men total. The unit had no official designation yet. The men called themselves something else. They called themselves Merill’s Marauders. The 5,37 Composite Unit was officially designated on May 28th, 1943, but the men had been training since April.

long-range penetration tactics, jungle survival, operations without supply lines. The unit was modeled after British Brigadier Ordinates Chindits, small mobile forces that could operate deep behind enemy lines for extended periods. George was assigned to the second battalion. His role was not officially listed as sniper. The army did not have formal sniper positions in its table of organization.

George was designated as a rifle platoon leader, but Colonel Ferry’s recommendation had followed him from Guadal Canal. Battalion command knew what George could do with a rifle. Training took place in central India. The terrain was different from Guadal Canal, but the principles remained the same. Heat, humidity, dense vegetation, limited visibility. The Burma jungle would be worse.

steeper terrain, heavier rainfall, and an enemy that knew the ground better than any American force. George modified his equipment for the Burma mission. The Winchester Model 70 had performed well on Guadal Canal, but that had been short-range operations with regular resupply. Burma would involve patrols lasting weeks, hundreds of miles through jungle. Every ounce of weight mattered.

George removed the Lyman Alaskan scope and replaced it with a lighter Weaver 330. The Weaver had the same 2 and 1/2 power magnification, but weighed 8 o less. He also replaced the wooden stock with a lighter synthetic version. The modifications reduced the rifle’s weight from 9 lb 12 oz to 8 lb 14 oz.

Not much, but over a twoe patrol carrying 60 lb of equipment, every ounce mattered. The Marauders entered Burma in February of 1944. Their mission was to advance through northern Burma and capture the Mitkina airfield. The airfield was critical for Allied supply routes into China. Japanese forces controlled the area with approximately 4,000 troops.

The Marauders would approach overland through terrain the Japanese considered impassible for large forces. Mountains, rivers, dense jungle, no roads, limited trails. The force would carry all supplies on their backs or with pack mules. No motorized transport, no artillery support, just rifles and mortars and the ability to move fast through impossible terrain.

George’s battalion began the march on February 24th. The first week covered 83 mi through mountainous jungle. Men collapsed from exhaustion. Malaria cases increased daily. The pack mules struggled with the terrain. Several had to be shot when they broke legs on steep descents. By March, the battalion had covered 217 mi. They had engaged Japanese forces 12 times.

Small skirmishes, ambushes, quick firefights followed by rapid withdrawal. The marauders were not meant to hold ground. They were meant to move, to harass, to cut supply lines and create chaos behind Japanese positions. George used his Winchester three times during the march. Once at 412 yds against a Japanese officer directing troops at a river crossing.

Once at 380 yard against a machine gun position. Once at 290 yard against a sniper who had pinned down a marauder patrol. Three shots, three kills. George never fired more than once per engagement. The Winchester’s report was distinctive, different from the Garand’s sharp crack. One shot announced his presence. A second shot would give the Japanese time to locate him. George learned to shoot and move immediately.

The march to Mitkina took 3 months. By late May, the Marauders had covered over 700 m. They had lost more men to disease than combat, malaria, dysentery, typhus. The unit that entered Burma with 5,300 men was down to fewer than 3,000 defectives. On May 17th, the Marauders captured Mitkina airfield.

The operation was a success, but the cost had been severe. The unit was combat ineffective. Too many casualties, too many sick, too much time in the jungle without rest or proper medical care. George survived the Burma campaign.

His Winchester survived, but the rifle that had proven so effective on Guadal Canal had been used only seven times in 3 months of operations. The Marauders rarely engaged in the kind of long range precision shooting that required a scoped rifle. Most combat was close-range ambushes at 50 yards or less, firefights in dense vegetation where you could barely see 30 ft. George realized something during those three months in Burma.

The Winchester Model 70 was an excellent rifle, perhaps the best bolt-action sporting rifle ever made. But modern warfare was changing. Semi-automatic rifles like the Garand were becoming standard. The next war would require different weapons, different tactics. But there would be no next war for George. Not immediately. By June of 1944, he was evacuated from Burma with the rest of the Marauders.

The unit was disbanded. George was reassigned to training duties in the United States. He never fired his Winchester in combat again. George returned to the United States in July of 1944. The Army promoted him to captain and assigned him to Fort Benning, Georgia. His job was training infantry officers in marksmanship and small unit tactics.

He taught the lessons he had learned on Guadal Canal and in Burma, how to move through jungle terrain, how to identify and engage targets at distance, how to operate independently without supply lines. He kept his Winchester Model 70. The rifle had traveled from Illinois to Tennessee to Guadal Canal to India to Burma to Georgia. It had killed at least 14 enemy soldiers in confirmed engagements, probably more. George had stopped counting after Burma.

The rifle sat in a foot locker in his quarters at Fort Benning. George rarely looked at it. The war had changed. The Pacific Islands were being retaken one by one. American forces were advancing through France and into Germany. The need for individual marksmen with privatelyowned rifles was fading.

The military was standardizing mass production, interchangeable parts, soldiers with identical equipment and identical training. George understood the necessity. Modern warfare required industrial scale. But something was being lost. The individual skill, the craftsman approach to soldiering.

the idea that a man with the right rifle and the right training could change the outcome of a battle. George was discharged from the army in January of 1947. Lieutenant Colonel, two Bronze Stars, one purple heart, combat infantry badge. He returned to Illinois and enrolled at Princeton University on the GI Bill. He studied politics, graduated with highest honors in 1950.

After Princeton, George spent four years at Oxford, then four years in British East Africa studying regional politics and institutions. He eventually settled in Washington, DC as executive director of the Institute of African-American Relations. Later, he joined the State Department’s Foreign Affairs Institute as a consultant and lecturer on African Affairs.

George never spoke publicly about Guadal Canal or Burma during those years. He had colleagues who knew he had served in the Pacific, but they did not know about Point Cruz. They did not know about the Japanese snipers. They did not know about the Winchester Model 70 that sat in a case in his home. In 1947, George decided to write down what had happened.

Not for publication, just for his own record. He wanted to document the weapons and tactics of jungle warfare while the details were still fresh. He wrote for 6 months. The manuscript grew to over 400 pages. A friend at the National Rifle Association read the manuscript and suggested publication. George was reluctant. The book was technical, detailed descriptions of rifles and ammunition and ballistics.

Not the kind of content that interested general readers, but the NRA convinced him. The book was published in 1947 under the title Shots Fired in Anger. It became a classic among firearms enthusiasts and military historians. The book described George’s experiences on Guadal Canal and Burma with clinical precision.

No embellishment, no hero worship, just facts and observations about what worked and what did not work in combat. The book is still in print today, still used as a reference by collectors and historians studying World War II smallarms. George’s descriptions of Japanese weapons remain some of the most detailed contemporary accounts available.

George lived to see the United States fight three more wars, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War. He watched the evolution of military rifles from the Garand to the M14 to the M16. He watched sniping become a formal military specialty with dedicated training and equipment. He watched the lessons of World War II being relearned and refined by new generations of soldiers.

John George died on January 3rd, 2009. He was 90 years old. The Winchester Model 70 that had killed Japanese snipers on Guadal Canal was donated to the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Virginia. It sits in a display case with a placard describing its history. Most visitors walk past without stopping. It looks like any other vintage hunting rifle, but it is not.

It is the rifle that proved a state champion marksman with a mail order scope could outshoot professionally trained military snipers. The rifle that cleared the point crews Groves in 4 days when an entire battalion could not do it in 2 weeks. The rifle that changed how the American military thought about individual marksmanship in modern warfare.

If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor, hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about riflemen who prove themselves with skill and courage. Real people, real heroism.

Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer, you’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here.

Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure John George doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

My husband texted me out of nowhere: “I’m done with us. I’m taking off to Miami with my 20-year-old girlfriend, and I took every last dollar from our joint account, lol.” I only replied: “Good luck.” By the time the truth hit him, everything was beyond repair…

When the message arrived, I was standing in the middle of the checkout line at a Target in Cleveland, holding…

I inherited $900,000 from my grandparents, while the rest of my family got nothing. Enraged, they banded together and demanded I vacate the house by Friday. Mom sneered, “Some people don’t deserve nice things.” I smiled and said, “You think I’d let that happen after everything I know about this family?” Two days later, they arrived with movers and smug grins—only to freeze when they saw who was waiting on the porch.

My name is Clare, and at 28, I had become intimately familiar with the corrosive nature of grief and greed….

At a family barbecue, my little girl fell from the playground and was rushed to the hospital in a coma. I was holding her hand when my son came up and whispered: “Mom… I know what really happened.” My heart stopped. “What did you see?” I asked him. He opened his mouth to speak, but before a single word came out, the hospital door burst open…

The smell of roasted corn and smoked meat still lingered on my hands when everything changed. We’d gathered at my…

“He crawled out of a forgotten basement with a broken leg, dragging his dying little sister toward the only ray of light left. His escape wasn’t just survival: it was a silent scream the world needed to hear.”

The darkness in the Brennans’ basement wasn’t just the absence of light: Oliver Brennan had begun to believe she was…

When I went to my ex-wife’s house to pick up our daughter, I noticed red marks on her back. Her new boyfriend just laughed and said, “They’re just little marks.” I smiled and replied, “Thank you… that helps me more than you think.” The girl didn’t want to take off her hoodie, but my ex ended up lifting the garment. Then I saw it: a massive mandala tattooed on her back. “She said she wanted to look strong, like in the movies,” my ex commented as if it were no big deal. But what happened next… was something I never imagined.

When I arrived at my ex-wife’s house to pick up our daughter, the last thing I expected was to feel…

During a family dinner, I stood up smiling and announced I was pregnant. The entire table fell completely silent; then, my mother-in-law suddenly burst out laughing and yelled: ‘She’s faking her pregnancy just to get money from us!’ Before anyone could react, she grabbed my hand and shoved me from the hotel rooftop ‘to prove’ I was faking it. Shattered and barely conscious, I woke up in the hospital with my husband beside me, pale as a ghost and trembling. But the moment the doctor walked in and opened his mouth, the words he said froze the entire room in absolute disbelief and horror.

“The moment I stood up during the family dinner, gently placing a hand on my stomach, I felt both nervous…

End of content

No more pages to load